Poor sleep hygiene, upper airway challenges, and other surmountable barriers are not ‘CPAP intolerance.’

By Donald E. Watenpaugh, PhD

Even though CPAP therapy definitively treats obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), adherence remains notoriously poor. That is in part because treating OSA with CPAP therapy often requires attention to much more than just…treating OSA with CPAP therapy.

A struggle that is quickly labeled as “CPAP intolerance” is, in most cases, a surmountable barrier (or series of barriers). In my experience, sleep apnea is often not a patient’s only sleep problem, and non-OSA sleep problems frequently interfere with CPAP therapy. Taking a holistic view of the patient’s sleep and circadian circumstances can resolve many cases of “CPAP intolerance.”

Here is an overview of common non-sleep apnea-related barriers to CPAP adherence.

Poor Sleep Hygiene

Poor sleep hygiene includes any behaviors people do that vex their sleep and, ultimately, vex their use of CPAP therapy.

For example, patients will say they can’t wear their CPAP mask because they need their glasses on to watch TV in bed. But then they fall asleep with their glasses on and without their sleep apnea treatment in place. (How many times must we explain no one “watches” TV with their eyes closed?) Candid discussions can help them weigh the cost of bad bedtime habits against the benefits of using their CPAP.

Comorbid Insomnia

OSA is a notoriously under-recognized cause of insomnia.1 We once treated an 8-year-old patient with intractable insomnia, behavioral problems, and poor grades who called using CPAP therapy “knockout gas.” Like many, his wake-sleep arousal threshold was so low that he needed to breathe to fall asleep! His social life and grades improved dramatically after starting therapy.

Compensatory behaviors for untreated sleep apnea—excessive caffeine use, evening “recliner naps,” nicotine use, and/or exclusion from the bedroom due to snoring come to mind—can also lead to insomnia.

Some people with insomnia say that CPAP exacerbates their sleeplessness. The good news is that cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia easily melds with CPAP coaching.2 Look, Mom, no pills!

In short, difficulty falling asleep is not “CPAP intolerance.” But inattention to insomnia (primary or secondary) may interfere with CPAP use.

Restless Legs Syndrome and Pain

Movement from bedtime restlessness and/or pain often persists into sleep. Patients with such problems frequently complain of CPAP interface instability and air leakage. They even sometimes blame CPAP for their restlessness. But no CPAP interface fits and seals well for someone writhing like a dervish in bed.

Thankfully, many treatment options exist for restless legs syndrome and sleep disturbance from pain. Opiates treat both, and medical cannabis is an emerging option.

Also, correcting hypovitaminosis D—a deficit more prevalent in dark-skinned people—is often “low-hanging fruit” in pain and sleep management.3

Parasomnias

Treatment of OSA often tempers the incidence and severity of parasomnia events. But breakthrough events may complicate treatment—and in some cases destroy equipment! Medication beyond just breathing may become necessary. Parasomnias do not cause CPAP intolerance.

Medication Timing

Medications that impact the sleep-wake state may facilitate or interfere with CPAP adherence.

While hypnotics, analgesics, and restless legs syndrome medications can be game-changers, if a patient complains the pills are not working, ask them when they take the drugs. They may take them immediately before lying down to sleep. Remind the patient to take the medication 30 to 60 minutes before bedtime (and possibly longer for some restless legs syndrome prescriptions).

More common scenarios involve wakefulness or restlessness from certain antihistamines, antidepressants, or stimulants taken late in the day. For example, a patient with insomnia who takes two Excedrin (130 milligrams of caffeine) near bedtime. A more complex example is methylphenidate for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD); because the drug’s half-life may exceed six hours, 25% of a dose taken in the early afternoon will remain bioactive after midnight. Don’t forget about non-prescription stimulants such as nicotine from tobacco or vaping.

What if a patient’s OSA contributes to a comorbid disorder (such as ADHD) that is treated with prescription medications? This raises the conundrum of prescriptions for symptoms of OSA that interfere with its treatment. Would treatment of OSA reduce or eliminate the need for certain medications? Such situations require communication with prescribers about more than just medication timing.

Nonetheless, inappropriate circadian timing of medications is not “CPAP intolerance.” It is an opportunity to teach patients and prescribers when to take medications to avoid interference with sleep.

Psychiatric Concerns

Severe depression sometimes presents with profound apathy, which includes lacking the motivation to use CPAP therapy. Even if the depression is secondary to sleep apnea, a vicious cycle between the two may require addressing the mood disorder first.

The same holds true for the pathologic fear of face coverings. Some of our patients have been distressed just at the sight of CPAP interfaces on mannequin heads in our clinic. They overcame such angst with self-paced, in-home desensitization using loaned equipment.4 Temporary anxiolytics may help.

Surprisingly, claustrophobic patients sometimes prefer full face masks because they allow comfortable breathing through the nose or mouth. Tuning of pressure level and mode to patient comfort is also critical. For example, some morbidly obese patients with claustrophobia quickly adapt to high-level BiPAP. After realizing that positive airway pressure helps them breathe, claustrophobic patients become some of sleep medicine’s most ardent advocates!

Patients with oppositional behavior come to appointments with a fortress-like maze of excuses for not using CPAP. The best way out of the maze may be to confront the behaviors instead.

Intractable claustrophobia or oppositional behavior may represent actual CPAP intolerance.

Upper Airway Challenges

When CPAP causes rhinitis or xerostomia, the usual suspects are unmanaged mouth venting or insufficient treatment pressure.

Improper equipment hygiene may be overlooked. For example, we found algae in a CPAP humidifier that had been placed near a sunny window. Alternately, soap fumes from incomplete rinsing can irritate oronasal mucosa. Patient-introduced additives like essential oils may also cause trouble.

Non-CPAP factors could cause upper airway symptoms as well. Postural gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) stimulates excess mucus production. Allergens that get to the eyes can cause upper airway symptoms. So we ask, “How old is your pillow? Mattress?” and “Are your bedding and laundry detergent hypoallergenic?” It is better to correct primary problems than treat downstream symptoms.

Sleep-related upper airway symptoms are not “CPAP intolerance.” Quite the contrary: The HEPA filtration and adjustable humidification provided by CPAP should be upper airway heaven. We have had patients use CPAP during the day not to nap but for respite from airborne allergens.

Insufficient Sleep

How can an elevated Epworth Sleepiness Scale score remain unchanged after starting CPAP? It could be due to changes in the patient’s sleep behavior. We have encountered patients who used their improved sleep quality to reduce their sleep duration. The net effect on their wakefulness was a wash.

Reassess self-reported sleep duration at follow-up visits, and compare it to baseline values. Do not immediately prescribe stimulants; no standard of practice recommends medications to facilitate a poor lifestyle.

Also Not ‘CPAP Intolerance’

Compiling an exhaustive list of all the potential problems that can frustrate CPAP use would take more space than available here, but a few other medical problems may challenge CPAP use include circadian dysrhythmias (compliance records can reveal these), postural GERD, menopausal hyperhidrosis, unaccustomed sleep postures imposed after surgery or during hospitalization, eye/facial/head surgery (for example, interface changes to accommodate cataract surgery), sleep-related seizures, upper extremity limitations (consider the TAP-PAP system), all-source cognitive impairment, nasolacrimal duct and other ocular complications, interface-induced periorbital edema (no patient wants bags under their eyes from treating a sleep problem), and nocturnal peritoneal dialysis.

Other inputs that may impact PAP use include pregnancy, breastfeeding, spouse/young children’s sleep, unsupportive family members, unsupportive caregivers (yes, this happens), socioeconomic healthcare disparities,5 shift work, frequent sleeping away from home (such as firefighters), situational need for battery power, possible accommodations for travel to high elevation (solutions could be acetazolamide or supplemental oxygen), unstable living situations, insurance changes, and pets chewing up masks.

Needless to say, none of the above constitute “CPAP intolerance.”

Helping patients overcome obstacles to CPAP use may seem like medical whack-a-mole, but it is rewarding. By treating the whole sleep/circadian patient, 96% of our patients prescribed CPAP use it an average of 86% of nights for 6.4 hours/night.

CPAP has been unjustly crucified. It’s well past time for its resurrection based on holistic sleep/circadian medical practice.

Low Adherence Expectations Lead to Poor Performance

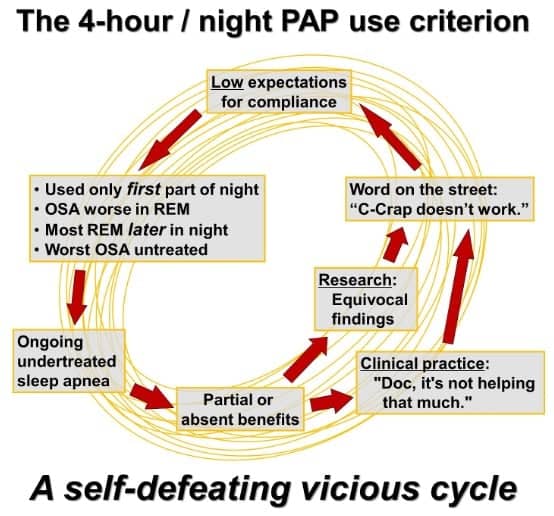

Sleep medicine continues to grapple with the ill-founded, self-defeating, yet deeply ingrained four-hour-per-night CPAP usage criterion.

How bad can this get? One durable medical equipment provider emphatically told patients to use CPAP four hours per night. An elderly couple set their alarm for four hours after bedtime so they would know when to discontinue treatment each night!

The literature is bloated with studies reporting minimal or zero benefits from CPAP therapy (including the SAVE study).6 But the compliance criterion in these studies is four hours per night or even less! It is analogous to a phase III clinical drug trial that employs an intentionally deficient dose that would control maybe half of the target disease’s primary pathophysiological mechanism. The rare CPAP outcomes studies that ensure full compliance produce unequivocally positive findings.7

Low expectations drive poor outcomes. The culture of sleep clinical care acts like using CPAP is like eating broken glass. It is not. We had several long sleepers with OSA who used CPAP with many benefits and zero problems. A 75-year-old male patient averaged 10.8 hours of use per day. A 56 year-old woman averaged 9.7 hours a day; about twice per month she exceeded 15 hours a day.

Think of it this way: What if oncologists had a highly effective noninvasive treatment for [cancer of your choice] with minimal risk of complications or side effects? Patients self-administered this treatment at home during sleep instead of undergoing daytime radiation or chemotherapy at a medical facility. Would oncologists embrace and encourage such a therapy?

Paradoxically, patient advocacy may save sleep medicine from itself. Twenty years ago, it was common to encounter people who “knew” OSA was a hoax. No more. Today, it’s common and, yes, inspiring to encounter people eager to share how nightly nightlong use of CPAP revitalized their lives.—DEW

References

- Janssen HCJP, Venekamp LN, Peeters GAM, et al. Management of insomnia in sleep disordered breathing. Eur Respir Rev. 2019 Oct 9;28(153):190080.

- Sweetman A, Lack L, Catcheside PG, et al Cognitive and behavioral therapy for insomnia increases the use of continuous positive airway pressure therapy in obstructive sleep apnea participants with comorbid insomnia: a randomized clinical trial. Sleep. 2019 Dec 24;42(12):zsz178.

- Herrero Babiloni A, De Koninck BP, Beetz G, et al. Sleep and pain: recent insights, mechanisms, and future directions in the investigation of this relationship. J Neural Transm (Vienna). 2020 Apr;127(4):647-60.

- Chernyak Y. Improving CPAP adherence for obstructive sleep apnea: A practical application primer on CPAP desensitization. MedEdPORTAL. 2020 Sep 15;16:10963.

- Roy S. What might be obstructive your patient’s CPAP adherence. Sleep Review 2023 March:6-7.

- McEvoy RD, Antic NA, Heeley E, et al; SAVE investigators and coordinators. CPAP for prevention of cardiovascular events in obstructive sleep apnea. N Engl J Med. 2016 Sep 8;375(10):919-31.

- Pamidi S, Wroblewski K, Stepien M, et al. Eight hours of nightly continuous positive airway pressure treatment of obstructive sleep apnea improves glucose metabolism in patients with prediabetes. A randomized controlled trial. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2015 Jul 1;192(1):96-105.

Illustration 142582162 © Ratz Attila | Dreamstime.com

Excellent article, Dr. Watenpaugh. We need a better word than intolerance for most of these patients. Of course, there’s another take when you see some tolerate oral devices after struggling with PAP. Sometimes, it actually is PAP creating their discontent.

Dr. Smith, thanks for your comments, and for ALL you do for sleep medicine! My main point is that a positive, holistic, problem-solving approach to CPAP use demonstrates that the huge majority of patients labeled “CPAP intolerant” are not. In other words, there’s no need for another word! Just a need for attentive thorough caregiving towards the very achievable goal of nightly nightlong CPAP use.

Think of it this way: In many cases, one could simply substitute “oral appliance therapy” for “CPAP” in the article. Are patients who don’t use their MAD for any correctible reason (sleep hygiene problems, rhinitis, insomnia, RLS, acute dental problems, bruxism, on and on) “MAD intolerant?” No. They just need help eliminating those obstacles. Thanks again!

Thank you, Sleep Review, and Dr. Watenpaugh, for shedding light on this under-discussed topic. “PAP disengagement” is a multidimensional problem. In our fragmented, often fractious system of healthcare delivery, our patients’ tendency to remain engaged is directly proportional to their understanding this web of complexity to allow them to feel engaged in the problem-solving process, as they navigate complications and competing diagnoses together. This is another field-testimonial supporting education for our patients that provides navigational agency. Well done!

Dr. McCarty, thanks for your thoughtful compliments! I couldn’t agree more that patient education is the essential foundation of everything we do. It enables them to, as you said, “navigate complications and competing diagnoses together.” Thanks again!

You cover a lot of great points. Another issue often overlooked is the impact of aerophagia. It’s not just “a little trapped gas” it can cause pain and discomfort to the point that patients abandon treatment. I have been a CPAP user for 15 years and have spent 3 years interviewing sleep apnea patients for my podcast “Sleep Apnea Stories”. The main takeaway is that we, as patients, want access to ALL the available treatment options. CPAP doesn’t work for every person, it would be great if we were given options like oral appliance therapy, hypoglossal nerve stimulation, surgeries with ENTs, double jaw surgery, bariatric surgery, eXciteOSA etc. without having to do all the research and seek them out ourselves.

Ms. Cooksey, you make a very important point! Another of the ways we achieved such high CPAP compliance in our patient population was to know when an alternative therapy may work better than CPAP for specific patients, and/or when CPAP was contraindicated. Just one example: If a patient with mild OSA was already using a mouthguard during sleep for bruxism, we would often recommend OSA treatment with a mandibular advancement device. They were pre-acclimated to wearing an oral appliance during sleep.

We proactively educated each patient about treatment options for THEIR OSA, including sometimes simple lifestyle modifications. We didn’t prescribe CPAP for them when we had more confidence in an alternative. Thanks again for your insights! BTW, I’ve used CPAP for 22 years and would love to be interviewed for your podcast. Be well!