The prevalence, possible etiological mechanisms, and suggested treatment order of comorbid insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea, as explained by a researcher on the team that coined the term ‘COMISA.’

By Alexander Sweetman, PhD

Physicians and scientists have long thought of insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) as two distinct sleep disorders with separate presenting features, consequences, treatments, and specialist care providers. But in recent years, there is burgeoning new research and clinical interest that looks at insomnia and sleep apnea together. That’s why, in 2017 my team at Flinders University of South Australia coined the term COMISA to describe comorbid insomnia and sleep apnea, and to spur new research focus and clinical attention in this area.1

Since then, we have proposed that insomnia and OSA share bidirectional relationships that increase their comorbidity, cause greater physical and mental health consequences, and impact the tolerability and efficacy of treatment for each condition alone.2 Now, science is unraveling why insomnia and OSA frequently co-occur, can result in higher morbidity compared to either disorder alone, and require unique management approaches.

COMISA Prevalence

The late Christian Guilleminault, MD, first described the comorbidity of insomnia and sleep apnea in 1973.3 Two articles in 1999 and 2001 reporting a high prevalence of COMISA in samples with insomnia4 and OSA,5 respectively, caught the attention of the global sleep medicine community.

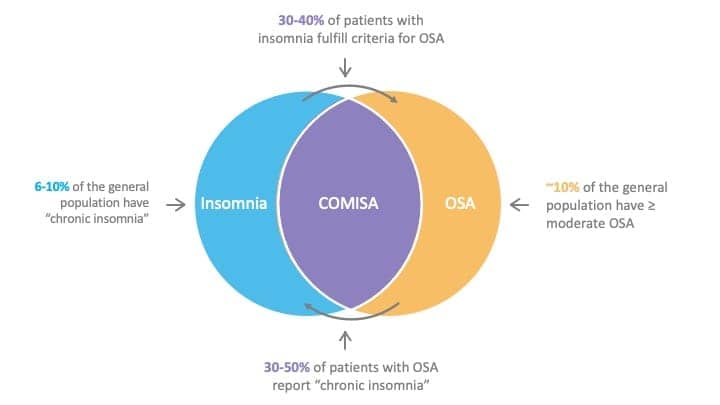

About 30% to 50% of people with OSA report clinically significant symptoms of insomnia, while 30% to 40% of people with insomnia have comorbid OSA.6-8 The comorbidity may be higher in specific populations including in sleep clinic settings (there may be a referral bias),5 those with treatment-resistant insomnia or OSA,9 and in military and veteran populations.10 Most studies have reported a higher prevalence of insomnia in those with OSA and a higher prevalence of OSA among those with insomnia (compared to those without the other disorder).8

Overall, the prevalence of COMISA in the adult general population varies between 1% and 7%, depending on sampling techniques and the measures and thresholds used.11-17

Collectively, this suggests COMISA is highly prevalent, impacting at least a third of people with insomnia or OSA.

Figure from Sweetman et al, 20212

Emerging Etiological Mechanisms

In some patients, it is possible that insomnia symptoms are secondary to the respiratory events—arousals and awakenings from untreated OSA. This would explain the reduction in insomnia symptoms among some COMISA patients when treated with CPAP therapy.18 Over time, repeated awakenings with surges in sympathetic activity may result in longer awakenings, as well as maladaptive behaviors. A pattern of “conditioned insomnia” may then form, which would develop functional independence of the OSA, reciprocally contribute to manifestations of OSA, and would require targeted insomnia treatment.

Insomnia may also exacerbate OSA in some patients. We have hypothesized that the state of physiological and cognitive arousal associated with insomnia may reduce the threshold for patients to arouse to stimuli.17 The respiratory arousal threshold is a known non-anatomical contributor to OSA severity. In people with an anatomical predisposition to airway collapse, a conditioned physiological arousal response of insomnia may reduce the threshold to awaken to minor respiratory events. This may explain the reduction in OSA severity following cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia (CBT-I).19

COMISA Linked to Mortality

Three recent epidemiological studies using the Sleep Heart Health Study,15 National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey,16 and Wisconsin Sleep Cohort20 data (a total sample size of 13,248) have reported that people with COMISA experience a 47% to 71% increased risk of all-cause mortality over 10 to 20 years of follow-up, compared to people with neither condition. Insomnia alone and OSA alone were not linked with increased risk of mortality in controlled models.

The association between COMISA and mortality needs more investigation. People with COMISA generally have worse sleep, daytime function, mental health, physical health, and quality of life compared to people with either insomnia alone, OSA alone, or neither condition. Recent studies by Lechat and colleagues21 and Jeon and colleagues22 highlight potential cardiovascular and mental health mediators of the relationship between COMISA and mortality.

Future research should investigate the effect of treatments for insomnia, OSA, and combination treatments on reducing markers of mortality risk in patients with COMISA.

Treatment Research

COMISA can be more complex to manage than insomnia or OSA alone. The symptoms and mechanisms of each condition may themselves create a barrier to treating COMISA.

For example, patients with COMISA are less likely to initially accept CPAP, and they use CPAP for fewer hours per night compared to patients with OSA alone.18 It is possible that CPAP exacerbates pre-existing insomnia symptoms or patients may see CPAP as a “threat” to their sleep (which many people with insomnia are protective of). An initial negative experience with CPAP may reduce patients’ likelihood to continue with therapy or trial CPAP in the future, so it may not be a suitable first treatment for all patients with COMISA.

Studies have also investigated the effect of non-CPAP therapies for OSA in patients with COMISA (such as surgery, nasal dilator strip therapy, and mandibular advancement devices).23-25 But comorbid insomnia symptoms may reduce adherence and response to these non-CPAP approaches too.26.27

CBT-I is the recommended first-line treatment for insomnia.28 Although CBT-I is effective in the presence of untreated OSA, the bedtime restriction component could increase levels of daytime sleepiness. If patients report excessive daytime sleepiness or increased sleepiness in specific situations (such as while driving), bedtime restriction instructions may need to be adapted.29

While sedative-hypnotic medicines are the most common approach to manage insomnia, they may exacerbate OSA severity in some patients. Targeted pharmacotherapy approaches for OSA is an emerging research area,30 but sedative-hypnotics are not presently recommended for the management of unselected OSA/COMISA.31

As insomnia symptoms reduce CPAP use, it may prove helpful to initially target insomnia symptoms with CBT-I. Our group,32 as well as Alessi and colleagues,33 report that CBT-I before CPAP improves CPAP acceptance and long-term use, compared to CPAP therapy alone, while Ong and colleagues34 report no effect of CBT-I on increasing CPAP use. Importantly, all three studies found that CBT-I improved insomnia symptoms.

Bjorvatn and colleagues observed no effect of a self-guided CBT-I book on insomnia symptoms or CPAP use.35 This may be due to limited use of the book and adherence to therapy recommendations.

One of the most important predictors of which treatment should be introduced first may be the patient’s chief complaint (that is, insomnia versus OSA symptoms). Although patient preferences are considered in the management of COMISA in clinical settings, future research studies should seek to systematically understand the chief presenting symptoms and motivation for treatment—and the role these play in different treatment COMISA approaches and outcomes.

Overall, it is recommended that patients with COMISA are treated for both insomnia and OSA, with consideration of their preferences, previous treatment/s, and sleepiness-related accident risks.

COMISA Research on the Horizon

Several ongoing studies are investigating the prevalence, etiology, and treatment approaches in patients with COMISA.

Among others, Osman36 and Brooker37 are investigating the presence of anatomical and non-anatomical phenotypic traits of OSA in patients with COMISA. It may be possible to use phenotypic traits of OSA (and insomnia) to guide the development and delivery of personalized treatments in the future.

We recently used Wisconsin Sleep Cohort data to investigate natural changes in the incidence, persistence, and remission of comorbid insomnia and OSA symptoms over time in the general population to better understand the onset sequence.38 Using these data to ask simple questions such as “Which disorder occurs first?” and “Does COMISA persist over time without treatment?” may help guide future treatment approaches and implementation efforts.

Research already suggests COMISA in adults is a prevalent and debilitating condition. Future studies should investigate the prevalence and management of COMISA in pediatric populations,39 as well as in specific sociodemographic groups and in samples with specific conditions (for example, patients with COMISA and chronic pain).

Also, although CBT-I is effective in the presence of untreated OSA, most patients with insomnia (including those with COMISA) are not able to access CBT-I due to a limited number of clinicians, high cost of therapy sessions, and long waiting times. To improve access to evidence-based CBT-I, self-guided digital CBT-I programs have been developed. At least two ongoing randomized controlled trials40,41 aim to investigate the feasibility, safety, and effectiveness of digital CBT-I programs in patients with COMISA.

To further inform COMISA treatment approaches, clinical trials in patients with OSA should include baseline and outcome measures of insomnia severity, while clinical trials in patients with insomnia should include objective or self-reported manifestations of OSA.

Alexander Sweetman, PhD, has had a specific interest in the prevalence, etiology, consequences, and treatment of COMISA since 2012. He manages a primary care sleep disorder education and implementation program with the Australasian Sleep Association and is an adjunct research fellow at the Adelaide Institute for Sleep Health at Flinders University in Australia.

References

1. Sweetman AM, Lack LC, Catcheside PG, et al. Developing a successful treatment for co-morbid insomnia and sleep apnoea. Sleep Med Rev. 2017 Jun;33:28-38.

2. Sweetman A, Lack L, McEvoy RD, et al. Bi-directional relationships between co-morbid insomnia and sleep apnea (COMISA). Sleep Med Rev. 2021 Dec;60:101519.

3. Guilleminault C, Eldridge FL, Dement WC. Insomnia with sleep apnea: a new syndrome. Science. 1973 Aug 31;181(4102):856-8.

4. Lichstein KL, Riedel BW, Lester KW, Aguillard RN. Occult sleep apnea in a recruited sample of older adults with insomnia. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1999 Jun;67(3):405-10.

5. Krakow B, Melendrez D, Ferreira E, et al. Prevalence of insomnia symptoms in patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Chest. 2001 Dec;120(6):1923-9.

6. Luyster FS, Buysse DJ, Strollo PJ Jr. Comorbid insomnia and obstructive sleep apnea: challenges for clinical practice and research. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010 Apr 15;6(2):196-204.

7. Zhang Y, Ren R, Lei F, et al. Worldwide and regional prevalence rates of co-occurrence of insomnia and insomnia symptoms with obstructive sleep apnea: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2019 Jun;45:1-17.

8. Sweetman A, Lack L, Bastien C. Co-morbid insomnia and sleep apnea (COMISA): prevalence, consequences, methodological considerations, and recent randomized controlled trials. Brain Sci. 2019 Dec 12;9(12):371.

9. Krakow B, Ulibarri VA, Romero EA. Patients with treatment-resistant insomnia taking nightly prescription medications for sleep: a retrospective assessment of diagnostic and treatment variables. Prim Care Companion J Clin Psychiatry. 2010;12(4):PCC.09m00873.

10. Wallace DM, Wohlgemuth WK. Predictors of insomnia severity index profiles in United States veterans with obstructive sleep apnea. J Clin Sleep Med. 2019 Dec 15;15(12):1827-37.

11. Lang CJ, Appleton SL, Vakulin A, et al. Co-morbid OSA and insomnia increases depression prevalence and severity in men. Respirology. 2017 Oct;22(7):1407-15.

12. Sweetman A, Melaku YA, Lack L, et al. Prevalence and associations of co-morbid insomnia and sleep apnoea in an Australian population-based sample. Sleep Med. 2021 Jun;82:9-17.

13. Sivertsen B, Björnsdóttir E, Øverland S, et al. The joint contribution of insomnia and obstructive sleep apnoea on sickness absence. J Sleep Res. 2013 Apr;22(2):223-30.

14. Vozoris NT. Sleep apnea-plus: prevalence, risk factors, and association with cardiovascular diseases using United States population-level data. Sleep Med. 2012 Jun;13(6):637-44.

15. Bjorvatn B, Pallesen S, Grønli J, et al. Prevalence and correlates of insomnia and excessive sleepiness in adults with obstructive sleep apnea symptoms. Percept Mot Skills. 2014 Apr;118(2):571-86.

16. Lechat B, Appleton S, Melaku Y, et al. Co-morbid insomnia and obstructive sleep apnoea is associated with all-cause mortality. Euro Resp J. 2021;in press.

17. Sweetman A, Lechat B, Appleton S, et al. Association of co-morbid insomnia and sleep apnoea symptoms with all cause mortality: Analysis of the NHANES 2005-2008 data. Sleep Epidemiology. 2022;in press.

18. Sweetman A, Lack L, Crawford M, Wallace D. Co-morbid insomnia and sleep apnea (COMISA): Assessment and management approaches. Sleep Medicine Clinics. 2021;in press.

19. Sweetman A, Lack L, McEvoy RD, et al. Cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia reduces sleep apnoea severity: a randomised controlled trial. ERJ Open Res. 2020 May 17;6(2):00161-2020.

20. Lechat B, Loffler KA, Wallace DM, et al. All-cause mortality in people with co-occurring insomnia symptoms and sleep apnea: Analysis of the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort. Nature and Science of Sleep. 2022;in press.

21. Lechat B, Appleton S, Melaku Y, et al. The association of co-morbid insomnia and obstructive sleep apnoea with prevalent cardiovascular disease and incident cardiovascular events. Journal of Sleep Research. 2022;in press.

22. Jeon B, Luyster FS, Callan JA, Chasens ER. Depressive symptoms in comorbid obstructive sleep apnea and insomnia: an integrative review. West J Nurs Res. 2021 Feb 3:193945921989656. Epub ahead of print.

23. Guilleminault C, Davis K, Huynh NT. Prospective randomized study of patients with insomnia and mild sleep disordered breathing. Sleep. 2008 Nov;31(11):1527-33.

24. Krakow B, Melendrez D, Sisley B, et al. Nasal dilator strip therapy for chronic sleep-maintenance insomnia and symptoms of sleep-disordered breathing: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep Breath. 2006 Mar;10(1):16-28.

25. Proothi M, Grazina VJR, Gold AR. Chronic insomnia remitting after maxillomandibular advancement for mild obstructive sleep apnea: a case series. J Med Case Rep. 2019 Aug 14;13(1):252.

26. Wallace DM, Wohlgemuth WK. 0558 Upper airway stimulation In US veterans with obstructive sleep apnea with and without insomnia: a preliminary study. Sleep. 2019;42(suppl_1):A222-3.

27. Machado MA, de Carvalho LB, Juliano ML, et al. Clinical co-morbidities in obstructive sleep apnea syndrome treated with mandibular repositioning appliance. Respir Med. 2006 Jun;100(6):988-95.

28. Qaseem A, Kansagara D, Forciea MA, et al; Clinical guidelines committee of the American College of Physicians. Management of chronic insomnia disorder in adults: a clinical practice guideline from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2016 Jul 19;165(2):125-33.

29. Sweetman A, McEvoy RD, Smith S, et al. The effect of cognitive and behavioral therapy for insomnia on week-to-week changes in sleepiness and sleep parameters in patients with comorbid insomnia and sleep apnea: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep. 2020 Jul 13;43(7):zsaa002.

30. Carter SG, Eckert DJ. Effects of hypnotics on obstructive sleep apnea endotypes and severity: Novel insights into pathophysiology and treatment. Sleep Med Rev. 2021 Aug;58:101492.

31. ASA. Sleep health primary care resource: Evidence-based resources and information to assess and manage adult patients with obstructive sleep apnoea and insomnia. 2021. Available at https://www.sleepprimarycareresources.org.au.

32. Sweetman A, Lack L, Catcheside PG, et al. Cognitive and behavioral therapy for insomnia increases the use of continuous positive airway pressure therapy in obstructive sleep apnea participants with comorbid insomnia: a randomized clinical trial. Sleep. 2019 Dec 24;42(12):zsz178.

33. Alessi CA, Fung CH, Dzierzewski JM, et al. Randomized controlled trial of an integrated approach to treating insomnia and improving the use of positive airway pressure therapy in veterans with comorbid insomnia disorder and obstructive sleep apnea. Sleep. 2021 Apr 9;44(4):zsaa235.

34. Ong JC, Crawford MR, Dawson SC, et al. A randomized controlled trial of CBT-I and PAP for obstructive sleep apnea and comorbid insomnia: main outcomes from the MATRICS study. Sleep. 2020 Sep 14;43(9):zsaa041.

35. Bjorvatn B, Berge T, Lehmann S, et al. No effect of a self-help book for insomnia in patients with obstructive sleep apnea and comorbid chronic insomnia – a randomized controlled trial. Front Psychol. 2018 Nov 29;9:2413.

36. Zheng JN, Tong B, Sweetman A, et al. The insomnia severity index is related to the respiratory arousal threshold in people with co-morbid insomnia and sleep apnoea (COMISA). Sleep Advances. 2022;in press.

37. Brooker E, Thomson L, Landry S, et al. O013 The pathogenesis of obstructive sleep apnea in individuals with comorbid insomnia and obstructive sleep apnoea (COMISA). SLEEP Advances. 2021 Oct;2(issue suppl_1):A6–7.

38. Sweetman A, LeChat B. Incidence, persistence and remission of co-morbid insomnia and sleep apnea (COMISA) over time in the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort data. Sleep Advances. 2022;in press.

39. Meira E Cruz M, Salles C, Seixas L, et al. Comorbid insomnia and sleep apnea in children: a preliminary explorative study. J Sleep Res. 2022 Aug 26:e13705.

40. Edinger J, Manber R. 363 The apnea and insomnia research (AIR) trial: An interim report. Sleep. 2021;44(issue suppl_ 2):A144-5.41. Sweetman A. Effect of digital cognitive behavioural therapy for insomnia (dCBTi) in people with co-morbid insomnia and sleep apnoea: A randomised waitlist controlled trial. 2022; https://www.anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?id=384648&isReview=true.

Illustration 240155950 © Kandella | Dreamstime.com