Although some still consider phototherapy an investigatorial treatment, evidence that it may safely help seasonal affective disorder is mounting.

There are many options for treating SAD. Although questions regarding the validity of SAD as a discrete syndrome persist and the therapeutic basis of light therapy continues to be investigated, the efficacy of light therapy is clear.

Diagnosis and Classification

SAD may occur in association with major depressive disorder (MDD), as described in the fourth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-IV)1—the “bible” of psychiatric disorders published by the American Psychiatric Association (APA). The DSM-IV describes SAD as a seasonal pattern of major depressive episodes that can occur in association with MDD, the criteria for which are shown in Table 1.

| Diagnostic Criteria for Major Depression

Five of the following symptoms must be present during the same 2-week period; must include at least one of the first two symptoms (as indicated by self-report or observation)* 1. Depressed mood most of the time * In patients with significant dysfunction or high level of distress in whom other factors (eg, drugs, medical conditions, bereavement) have been excluded. Adapted from: American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. |

Dysfunction in social or occupational settings or a high level of subjective distress distinguishes depression from temporary sadness, which is a normal part of the human experience. In persons who experience excessive sadness, levels of functioning and distress are disproportional to life events. Clues to depression include a previous depressive illness or suicide attempt, a family history of mood disorder, lack of social support, stressful life events, abuse of alcohol and/or other substances, and concurrent chronic medical disease, pain, and/or disability. The DSM-IV describes SAD as a “specifier,” referring to the seasonal pattern of major depressive episodes that can occur within MDD (see Table 2 on page 46).1

Etiology and Epidemiology

There have been numerous community-based investigations of the epidemiology of SAD.2-7 These surveys estimate that 4% to 6% of the general population experience full-blown SAD, and another 10% to 20% have features consistent with a diagnosis of SAD.2,3,6,7 In children and adolescents, the incidence of SAD is much less. Based on the results of several epidemiologic studies, the prevalence rate in children is believed to be in the range of 1% to 5%.4,5

Interestingly, the prevalence of SAD in Alaska is similar to that at much lower latitudes.3 Williams and Schmidt reported that 20% of patients treated for recurrent depression at a northern Canadian mental health center (latitude, 54 to 60 degrees) met the operational criteria for winter depression.8 They also noted that this incidence rate was similar to that reported at lower latitudes. Based on these and other studies, there does not appear to be a major association between latitude (ie, the amount of daylight each day) and the prevalence of SAD.

In community surveys, SAD is about four times more common in women than in men. The average age of onset is roughly 23 years.9 The risk of SAD appears to decrease with age.2

There is some controversy with regard to the roles of various “risk factors” for SAD. Blazer and colleagues reported that persons with SAD tend to be more educated and have greater incomes than those without the condition.2 The same investigators reported a greater incidence of SAD among persons who lived in rural compared to urban settings.2 These findings need to be confirmed in other surveys and in other parts of the world.

Pathophysiologic Theories

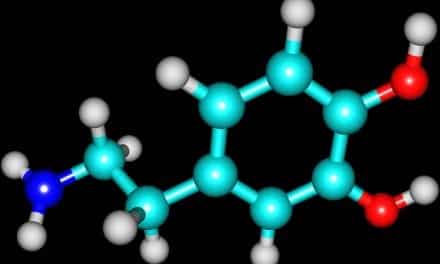

In 1984, Norman Rosenthal, a psychiatrist at the National Institute for Mental Health, published a paper on the use of bright light therapy in patients with SAD.10 Since then, a large number of studies have confirmed the value of light therapy in SAD and have added to our understanding of the pathophysiology of the condition. It is believed that SAD is caused by a biochemical imbalance in the brain due to the shortening of daylight hours and the lack of sunlight in winter. Bright light has been shown to suppress nighttime secretion of the hormone melatonin.11 An area of the brain near the visual pathway—the suprachiasmatic nucleus—responds to light by sending out a signal to suppress the secretion of melatonin.12

Studies in patients with SAD have focused on deviations in melatonin levels and on the pattern of melatonin secretion as possible causative factors. Persons with SAD may have impaired serotonin function in neurons leading to the suprachiasmatic nucleus, resulting in impaired melatonin secretion at night.12

Another pathogenic theory revolves around the concept of circadian rhythms (biologic variations within the 24-hour day). Investigators have shown that “phase shifting”—the shifting of the internal circadian cycle to an earlier or later clock time—can be created by exposure to bright light.13 The direction and magnitude of the phase shifting depend on when the bright light occurs within the cycle. The phase-shift hypothesis of SAD postulates that the therapeutic effect of light in SAD is due to a corrective phase shifting of endogenous circadian rhythms.13 According to this hypothesis, exposure to bright light must be timed appropriately within the circadian cycle to correct a specific phase shift. For example, morning exposure to bright light should correct a phase-delayed circadian rhythm, whereas evening light exposure should worsen these rhythms. Several studies have found that patients with SAD have a phase delay in circadian rhythms that can be corrected with morning bright-light treatment.14-18

The precise relationship between melatonin levels and circadian rhythms is unclear. It is believed that melatonin levels may indicate circadian phase. Several investigators have evaluated the use of melatonin in the treatment of SAD. Results have been mixed. In a study performed by Wirz-Justice and Anderson, neither nighttime nor morning melatonin administration had any effect on SAD symptoms.19 In contrast, Lewy and colleagues reported beneficial effects of low-dose melatonin administration times during the afternoon to provide a circadian phase advance.20

Treatment

Persons who suffer from SAD do not need to wait for the spring months to overcome their feelings of depression. For mild symptoms, spending time outdoors during the day or arranging homes and workplaces to receive more sunlight may be helpful. Regular exercise—particularly outdoor activity—may help because exercise can sometimes relieve depression. One study found that a 1-hour walk in winter sunlight was as effective as 2.5 hours under bright artificial light in relieving the symptoms of SAD.21

Light Therapy

For more severe symptoms, light therapy (phototherapy) may help. It involves daily scheduled exposure to bright artificial light, which may suppress the secretion of melatonin by the brain.12 Numerous studies and meta-analyses have demonstrated the efficacy of light therapy in alleviating the symptoms of SAD.22-27 According to the Seasonal Affective Disorder Association, light therapy should be used daily in the winter months, starting in early autumn when the first symptoms appear (as well as during symptomatic periods in the summer months).28

Various devices used in light therapy include fluorescent light boxes, a light box that uses incandescent light, a portable and flexible fluorescent light lamp, an incandescent head-mounted unit (“light visor” or “light cap”), and a “dawn simulator” device. A recent addition to the light therapy armamentarium is a device that incorporates white light-emitting diode technology, which allows a compact, bright light delivery system.

In general, light therapy is initiated with a 10,000-lux light box directed toward the patient at a downward slant. (Lux is the unit of measuring the illumination intensity of light.) Fluorescent light is often preferred over incandescent because the small point source of the latter is more conducive to retinal damage. The patient’s eyes should remain open throughout the treatment session, although staring directly into the light source is not recommended. The patient should start with a single 10- to 15-minute session per day, gradually increasing the session duration to 30 to 45 minutes. Sessions should be increased to twice per day if symptoms worsen. Ninety minutes a day is the conventional daily maximum duration of therapy, although there is no reason to limit the duration of sessions if side effects are mild.30

No particular time of day appears to be optimal for light therapy. Some studies have reported the superiority of morning sessions,17 while others have shown no significant difference between times of administration.31 Hence, when deciding what time of day to administer light therapy, consideration should be given to convenience and patient preference.

There is emerging evidence that the dose of light is important. Most controlled studies have shown that bright light is superior to dim light in the treatment of SAD.32-34 In humans, the suppression of melatonin generally requires at least 2,000 lux.12 Studies of 10,000-lux fluorescent light given for 30 minutes per day produced similar results to protocols employing 2,500 lux for 2 hours.32,35 The 10,000-lux light box has thus become the standard in clinical practice.

When light therapy is properly administered, most patients tolerate it well and have few adverse events. Common side effects, which occur in about 19% of patients,29 include photophobia, headache, fatigue, and irritability. If light therapy is administered too late in the day, insomnia may be a problem.36 In persons with manic depressive disorders, skin that is sensitive to light, and/or medical conditions that make the eyes vulnerable to light damage, light therapy should be used with caution. Tanning beds should not be used to treat SAD. The light sources in tanning beds are high in ultraviolet rays, which can damage both the eyes and the skin.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) considers light boxes Class III medical devices—the most stringent regulatory category for devices. Therefore, the FDA has not given final approval for manufacturers to market light boxes for the treatment of SAD. In 1993, the FDA entered into a “consent decree” that permits light box manufacturers to market light boxes in the United States provided that no significant therapeutic claims are made (ie, “light boxes are curative”). According to the FDA, as long as no therapeutic claims are being made by light box manufacturers, they are considered an “alternative medicine” and, therefore, may be dispensed in the United States without a prescription. Since 1997, the FDA has issued at least one warning letter to remove therapeutic claims from labeling. In 1998, the FDA convened a small, “informal” group to discuss health care policy. During this meeting, it was determined that light boxes, and their relationship to SAD, did not pose a “significant danger” to the public. In addition, the FDA is “not aware of any adverse events as a result of light box therapy.”29

In general, the price of a light therapy device ranges between $200 and $500, depending on the features of the unit.37 Some insurance companies may reimburse all or a portion of the cost of a light therapy device, if a proper diagnosis was made and the treatment was prescribed by a qualified health professional. Some manufacturers offer a rental program for a trial period.

| Specific Criteria for Seasonal Affective Disorder.

1. Regular temporal relationship between the onset of major depressive episodes and a particular time of the year (unrelated to obvious season-related psychosocial stressors) Adapted from: American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994. |

Other Treatments

Research has shown that antidepressant medications—particularly selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) such as fluoxetine, paroxetine, and sertraline—can relieve the symptoms of SAD.38,39 Some patients may prefer to take a pill because it is less time-consuming than sitting in front of a light box. Other individuals may need a combination of light therapy and medication in order to control symptoms. For patients with SAD and spring-summer mania, a mood stabilizer such as lithium may be useful.

The use of non-antidepressant medications for the treatment of SAD is controversial. Medications such as propranolol, L-tryptophan, hypericum, and melatonin require further study before they can be recommended for use in SAD.

Clinical-trial data evaluating the efficacy of psychotherapy specifically for SAD is lacking; however, in general, psychotherapy can be a useful adjunct for the management of depression. The efficacy of psychotherapy for depression is difficult to ascertain because of the challenges in conducting research and evaluating results. Studies usually have involved a select population of motivated individuals with the less severe forms of depression. Behavioral, cognitive, and interpersonal psychotherapies have all shown efficacy rates of 40% to 50%.40 Some comparative studies have shown that psychotherapy is more effective than antidepressant drug therapy,40 except in patients with a type of depression called melancholic depression, in whom response to medication is much better. Generally, outcome is improved when antidepressant treatment and psychotherapy are combined.

Conclusion

Although light therapy is still considered by the FDA to be an investigational treatment, numerous well-designed clinical trials have demonstrated its efficacy and safety in patients with SAD, and it is currently recognized as a first-line treatment modality. Research has also shown that antidepressants, with or without adjunctive psychotherapy, can be a safe and effective treatment of SAD. Further research is needed to establish the usefulness of non-antidepressant medicatiaons for the treatment of SAD.

John D. Zoidis, MD, is a contributing writer for Sleep Review.

References

1. American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 1994.

2. Magnusson A, Partonen T. The diagnosis, symptomatology, and epidemiology of seasonal affective disorder. CNS Spectr. 2005;10:625-634.

3. Rosen L, Knudson KH, Fancher P. Prevalence of seasonal affective disorder among US Army soldiers in Alaska. Mil Med. 2002;167:581-584.

4. Carskadon MA, Acebo C. Parental reports of seasonal mood and behavior changes in children. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1993;32:264-269.

5. Swedo SE, Pleeter JD, Richter DM, et al. Rates of seasonal affective disorder in children and adolescents. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1016-1019.

6. Haggag A, Eklund B, Linaker O, Gotestam KG. Seasonal mood variation: an epidemiological study in northern Norway. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1990;81:141-145.

7. Kasper S, Wehr TA, Bartko JJ, Gaist PA, Rosenthal NE. Epidemiological findings of seasonal changes in mood and behavior. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1989;46:823-33.

8. Williams RJ, Schmidt GG. Frequency of seasonal affective disorder among individuals seeking treatment at a northern Canadian mental health center. Psychiatry Res. 1993;46:41-45.

9. Sohn CH, Lam RW. Treatment of seasonal affective disorder: unipolar versus bipolar differences. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2004;6:478-485.

10. Miller AL. Epidemiology, etiology, and natural treatment of seasonal affective disorder. Altern Med Rev. 2005;10:5-13.

11. Aschoff J. Circadian timing. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1984;423:442-468.

12. Lewy AJ, Wehr TA, Goodwin FK, Newsome DA, Markey SP. Light suppresses melatonin secretion in humans. Science. 1980;210:1267-1269.

13. Lewy AJ, Sack RL, Miller LS, et al. The use of plasma melatonin levels and light in the assessment and treatment of chronobiologic sleep and mood disorders. J Neural Trans. 1986;21(suppl):311-322.

14. Avery DH, Dahl K, Savage MV, et al. Circadian temperature and cortisol rhythms during a constant routine are phase-delayed in hypersomnic winter depression. Biol Psychiatry. 1997;41:1109-1123.

15. Dahl K, Avery DH, Lewy AJ, et al. Dim light melatonin onset and circadian temperature during a constant routine in hypersomnic winter depression. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993;88:60-66.

16. Endo T. Morning bright light effects on circadian rhythms and sleep structure of SAD. Jikeikai Med. 1993;40:295-307.

17. Sack RL, Lewy AJ, White DM, Singer CM, Fireman MJ, Vandiver R. Morning vs evening light treatment for winter depression: evidence that the therapeutic effects of light are mediated by circadian phase shifts. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1990;47:343-351.

18. Postolache TT, Oren DA. Circadian phase shifting, alerting, and antidepressant effects of bright light treatment. Clin Sports Med. 2005;24:381-413.

19. Wirz-Justice A, Anderson J. Morning light exposure for the treatment of winter depression: the true light therapy? Psychopharmacol Bull. 1990;26:511-520.

20. Lewy AJ, Bauer VK, Cutler NL, Sack RL. Melatonin treatment of winter depression: a preliminary study. Psychiatry Res. 1998;77:57-61.

21. National Mental Health Association. Depression/Seasonal Affective Disorder. Alexandria, Va: National Mental Health Association; 2001. Available at: http://www.nmha.org/infoctr/factsheets/27.cfm. Accessed August 3, 2002.

22. Leppamaki SJ, Partonen TT, Hurme J, Haukka JK, Lonnqvist JK. Randomized trial of the efficacy of bright-light exposure and aerobic exercise on depressive symptoms and serum lipids. J Clin Psychiatry. 2002;63:316-321.

23. Koorengevel KM, Gordijn MC, Beersma DG, et al. Extraocular light therapy in winter depression: a double-blind placebo-controlled study. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:691-698.

24. Eastman CI, Young MA, Fogg LF, Liu L, Meaden PM. Bright light treatment of winter depression: a placebo-controlled trial. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:883-889.

25. Terman M, Terman JS, Ross DC. A controlled trial of timed bright light and negative air ionization for treatment of winter depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1998;55:875-882.

26. Wesson VA, Levitt AJ. Light therapy for seasonal affective disorder. In: Lam RW, ed. Seasonal Affective Disorder and Beyond: Light Treatment for SAD and Non-SAD Conditions. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Press; 1998:45-90.

27. Terman M, Terman JS, Quitkin FM, McGrath PJ, Stewart JW, Rafferty B. Light therapy for seasonal affective disorder: a review of efficacy. Neuropsychopharmacology. 1989;2:1-22.

28. Seasonal Affective Disorder Association. Treating Seasonal Affective Disorder (SAD). Steyning, England: Seasonal Affective Disorder Association; 2002. Available at: http://sada.org.uk/treat.htm. Accessed August 19, 2005.

29. Lam RW, Tam EM, Gorman CP, et al. Light treatment. In: Lam RW, Levitt AJ, eds. Canadian Consensus Guidelines for the Treatment of Seasonal Affective Disorder. Vancouver, Canada: Clinical & Academic Publishing; 1999:64-88.

30. Rosenthal NE. Light therapy: theory and practice. Primary Psychiatry. September-October 1994:31-33.

31. Wirz-Justice A, Graw P, Krauchi K, et al. Light therapy in seasonal affective disorder is independent of time of day or circadian phase. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 1993;50:929-937.

32. Magnusson A, Kristbjarnarson H. Treatment of seasonal affective disorder with high-intensity light: a phototherapy study with an Icelandic group of patients. J Affect Disord. 1991;21:141-147.

33. Isaacs G, Stainer DS, Sensky TE, Moor S, Thompson C. Phototherapy and its mechanisms of action in seasonal affective disorder. J Affect Disord. 1988;14:13-19.

34. James SP, Wehr TA, Sack DA, et al. Treatment of seasonal affective disorder with light in the evening. Br J Psychiatry. 1985;147:424-428.

35. Terman M, Terman JS, Schlager D, et al. Efficacy of brief, intense light exposure for treatment of winter depression. Psychopharmacol Bull. 1990;26:3-11.

36. Terman M, Terman JS. Light therapy for seasonal and nonseasonal depression: efficacy, protocol, safety, and side effects. CNS Spectr. 2005;10:647-663.

37. Saeed SA, Bruce TJ. Seasonal affective disorders. Am Fam Physician. 1998;57:1340-1346, 1351-1352.

38. Lam RW, Gorman CP, Michalon M, et al. Multicenter, placebo-controlled study of fluoxetine in seasonal affective disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 1995;152:1765-1770.

39. Moscovitch A, Blashko CA, Eagles JM, et al. A placebo-controlled study of sertraline in the treatment of outpatients with seasonal affective disorder. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2004;171:390-397.

40. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Treatment of Major Depression: Volume 2. Treatment of Major Depression, Clinical Practice Guideline No 5. Rockville, Md: Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; 1993. AHCPR Publication No. 93-0551.