A University of Chicago research team found that targeting a specific gene product may lead to nonsurgical treatment options for children with OSA.

A new study from the University of Chicago found that a specific gene product may be responsible for the proliferation of adenotonsillar tissue that can cause pediatric OSA, leaving researchers to conclude that children with OSA may one day be able to have an injection or use a throat spray instead of getting their tonsils removed to cure their snoring.

"We found that in the tonsil tissues of children with OSA, certain genes and gene networks were overexpressed," said lead researcher David Gozal, MD, professor and chair of the Department of Pediatrics. "We believe that the results of this gene overexpression is increased proliferation of the adenotonsillar tissues, which in turn can cause partial or complete obstruction of the upper airways during sleep."

To identify potential nonsurgical alternatives to treat OSA in children, Gozal and colleagues recruited 18 children with OSA and 18 age-, gender-, and ethnicity-matched children with recurrent tonsillar infections (RI), all of whom underwent surgery to have their tonsils removed. The tonsil tissue from each subject was analyzed for relative expression of the 44,000 known genes in the human genome. The researchers then further analyzed the gene pathways to determine which changes may represent differences with a high likelihood of impact on cellular proliferation.

"We identified 47 genes and among those, two specific genes, both phosphatases, which are known to be very important at regulating communication in cells,” said Gozal. “Then we looked at the expression of the phosphatase protein and found that children with OSA have a higher level of phosphatases in the tonsils."

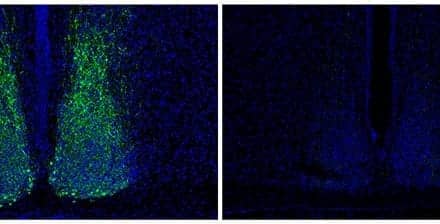

In particular, they focused on one protein called phosphoserine phosphatase (PSPH) that was expressed in children with OSA, but almost never expressed in the children with RI.

Gozal and his team found that introducing calyculin, a phosphatase inhibitor, reduced the cell proliferation and increased programmed cell death, or apoptosis, a process by which cells self-regulate, in the tonsils of OSA patients.

"Together, these observations suggest that PSPH is a logical therapeutic target in reversing adenotonsillar enlargement in pediatric OSA," wrote Gozal.

"The next direction is to identify if selective clones of proliferating cells that may be affected by PSPH or by another of the discovered target genes with the intent of developing a nonsurgical alternative treatment to surgery for OSA in children," said Gozal. "If there is a subgroup of cells that have specific markers, then we may be able to develop a therapy that could be specifically targeted to these cells."

The findings appear online ahead of print publication in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine.