More primary care physicians (PCPs) are getting involved in diagnosing obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) as home sleep testing companies continue their outreach to this market. Generally, attendees that I spoke with at the 2012 Associated Professional Sleep Societies (APSS) conference acknowledge this trend and have therefore begun to embrace home sleep testing for use in their practice. Simply embracing home testing is not enough. As more PCPs become involved with home testing, sleep professionals need to measure outcomes.

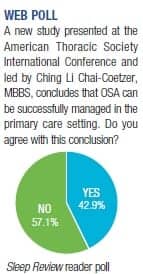

Studies are now showing that patients with moderate-to-severe OSA can be successfully managed in a primary care setting by appropriately trained PCPs and community-based nurses.

According to Ching Li Chai-Coetzer, MBBS, the lead author of one such study, “With the rise in demand and growing waiting lists for sleep physician consultation and laboratory-based sleep services, there has been increasing interest in development of ambulatory strategies for the diagnosis and management of OSA involving home sleep monitoring and auto-titrating continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP). While previous studies have demonstrated that ambulatory models of care for OSA in specialist settings can produce patient outcomes that are comparable to laboratory-based management, this is the first randomized controlled study to be conducted in primary care.” Chai-Coetzer is based at the Adelaide Institute for Sleep Health at Repatriation General Hospital in Australia.

For the study, the team randomized 155 patients to either care in the sleep center or management in a primary care setting. “At 6 months, mean change in Epworth sleepiness scale (ESS) scores, the primary outcome measure of the study, was similar in the two groups (4.9 in the primary care group vs 5.1 in the specialist group),” said Chai-Coetzer.

In addition to similar changes in ESS scores at 6 months, mean change in Functional Outcomes of Sleep Questionnaire (FOSQ) score was similar in the two groups (2.3 in the primary care group vs 2.7 in the specialist group), as was compliance with CPAP. Mean daily use of CPAP was 4.8 (±2.1) hours in the primary care group and 5.4 (±1.8) hours in the specialist group.

Furthermore, within-study costs for primary care management were lower than those for specialist care, with significant savings per patient.

With studies showing cost savings and comparable outcomes, it becomes imperative that along with shifting to a chronic disease management specialty, sleep centers track outcomes. “The key in deploying any approach to diagnosis and management of sleep apnea is ensuring quality outcomes, including CPAP compliance,” says Allan I. Pack, MBChB, PhD, founder and director of the Center for Sleep and Respiratory Neurobiology (CSRN) at the University of Pennsylvania Medical Center. “Sleep medicine is not a diagnostic discipline, it is a case management discipline. Our accreditation standards for integrated sleep centers should reflect this with outcomes of care being the primary measure that is used to assess quality and should be the basis of accreditation.”

Without outcome measures, labs are left with little to show in terms of how successful they are in managing patients. This opens the door for more PCPs to manage OSA, potentially cutting the sleep lab off from the care of patients with OSA. This is not in the best interest of the patient. Sleep professionals have invested years into improving the lives of patients with sleep-disordered breathing. Demonstrating outcomes is your opportunity to show your investment in patient care is paying off.

—Franklin A. Holman

[email protected]