Standardization of multiple sleep latency tests and maintenance of wakefulness tests will increase the value of results.

By Jane Kollmer

New guidance issued by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM) takes an updated look at the recommended protocols for assessing daytime sleepiness and alertness in adults.

The multiple sleep latency test (MSLT) measures the time it takes an individual to fall asleep in a quiet environment during the day. It is calculated over a series of nap opportunities. The faster the patient falls asleep, the greater the daytime sleepiness. The MSLT is used in the diagnosis of narcolepsy and idiopathic hypersomnia, and it can help assess ongoing sleepiness after the treatment of other sleep disorders such as obstructive sleep apnea.

The maintenance of wakefulness test (MWT) measures an individual’s ability to stay awake. For this test, the patient is in a quiet and dim environment and tries to stay awake. The MWT is used to evaluate response to treatment for disorders associated with excessive sleepiness and to assess alertness in individuals who must remain awake for safety reasons.

The guidance serves as an update to recommendations made by the AASM in 2005. The changes to the protocols for both sleep laboratory-based tests cover patient preparation, medication and substance use, sleep prior to testing, test scheduling, optimum test conditions, and documentation. They were written by a task force of clinical experts in sleep medicine and based on expert consensus.

Raman K. Malhotra, MD, president of the AASM and professor of neurology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, provided oversight and direction to the development of the guidance.

“The main goal is to allow practitioners to have an updated protocol on how to run these two studies,” he says. “A lot has changed since 2005, as far as different factors that can affect sleep, whether it’s new medicines or the prevalence of cell phones and electronic devices, and the group felt it was important to address them to allow for a standard approach for what to do with patients being tested for these conditions.”

MSLT Protocol Changes

One of the task force’s concerns was repeated MSLTs resulting in different sleep latency measures, according to one of the study authors, Donna Arand, PhD, associate professor of neurology at Wright State University Boonshoft School of Medicine.

“We felt by making minor changes in the protocol or giving more guidance, we could eliminate some of that variability that people were reporting,” Arand says.

The MSLT measures a patient’s propensity to fall asleep under standardized conditions. To acquire reliable data, it is essential the patient get adequate sleep before the test. For two weeks leading up to the MSLT, it is now recommended the patient keep a sleep diary, with or without actigraphy. This differs from the 2005 guidelines, which suggested seven days was sufficient.

“We felt that having a longer timeline might help identify inadequate sleep since it would also include two weekend periods where there can be more variability,” Arand says.

The AASM recommends a minimum of 7 hours of time in bed with at least 6 hours of sleep to develop consistency in sleep patterns, which Arand says may ensure more consistency in mean sleep latency.

Another change calls for ending stimulating activities, including the use of electronic devices, 30 minutes before testing. Previous practice parameters allowed some activities to continue up to 15 minutes prior to testing.

“We dealt with the fact that now cell phones and laptops are everywhere, which they weren’t necessarily in 2005,” Arand says. Recent studies have shown that using electronic devices before bedtime may negatively impact sleep as the blue-wavelength light they emit can suppress melatonin and stimulate brain activity.

Although it is not a new practice to conduct the MSLT immediately following polysomnography (PSG), the authors say there is no need for the patient to change their clothing between tests. What’s more, not all of the electroencephalography (EEG) leads need to be removed before the MSLT. The new guidelines recommend keeping on the frontal EEG leads—which have become standard for night-time studies—because the recording is useful in scoring sleep stages for the MSLT.

The other changes recommended pertain to factors that could confound MSLT or MWT results. For patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), the revised protocol states they should adhere to their normal treatment leading up to and during the daytime studies.

Malhotra says, “The concern was that if someone was only partially using their CPAP for their sleep apnea that you could get an inappropriately positive study for narcolepsy because their sleep apnea is not treated.”

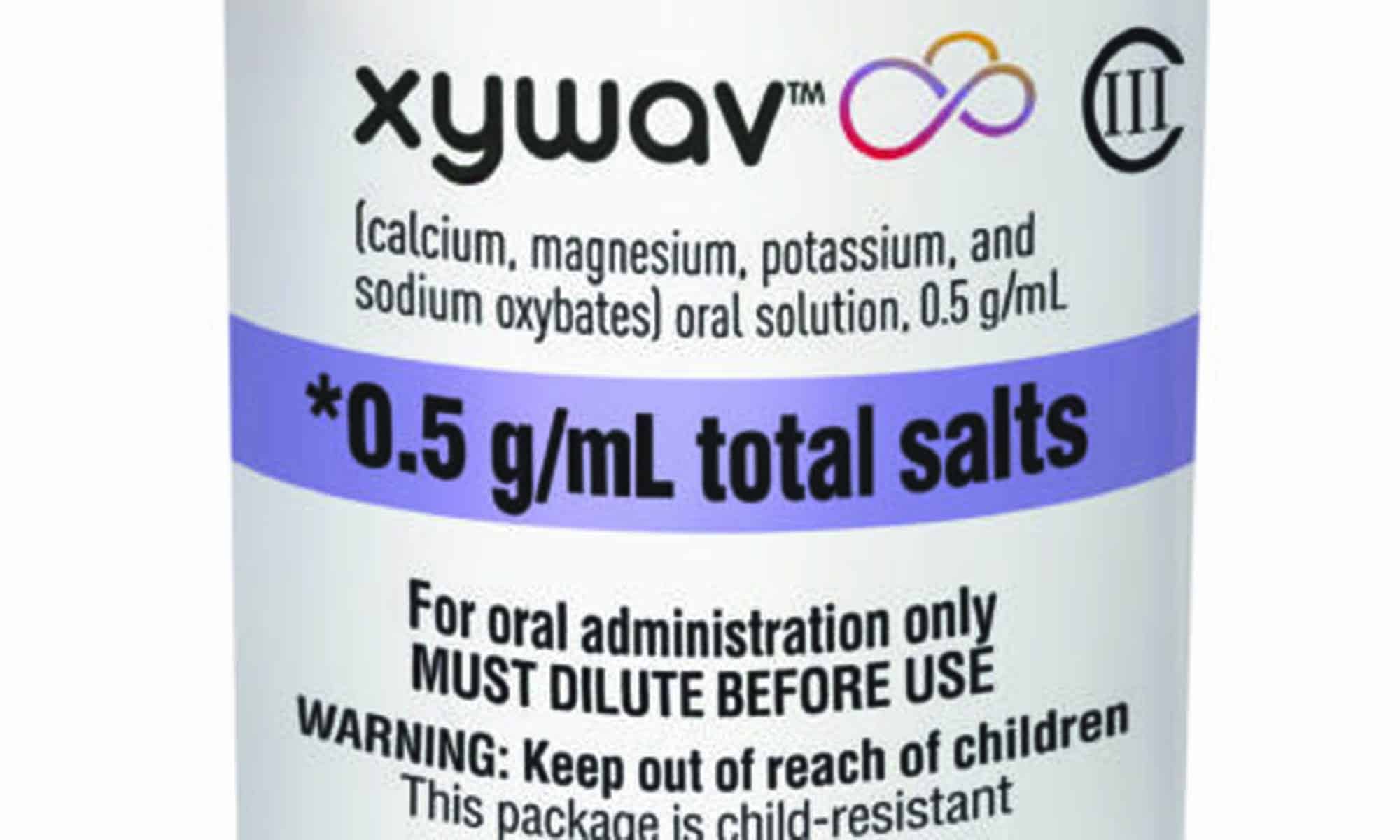

Medications with alerting, sedating, and/or REM-modulating properties were also addressed in greater detail in the updated protocols. Patients who report excessive daytime sleepiness are commonly being treated with stimulants or antidepressants for depression, anxiety, inattention, or fatigue. Because many of these medications may confound MSLT results, experts in 2005 recommended these drugs be discontinued two weeks before the test. But some drugs have a longer half-life and stay in the system for a longer period, and some may require less time to wash out.

Further complicating the issue is that stopping medications may create adverse outcomes for an individual patient, which could mean the risk outweighs the benefit. Therefore, clinical judgment should be used regarding changes to medications that could impair patient safety.

The task force suggests that clinicians and patients work together to develop a plan for managing medications to minimize disruption to the patient’s life and avoid unintended consequences such as withdrawal.

Sleep researcher Alyssa Cairns, PhD, who was not involved in creating the updated protocols, says, “The practitioner and the patient should talk about this very candidly and come up with a plan to taper off medications in order to have an accurate result.”

Addressing the concerns around medication was an important aspect of the new guidance because a report indicated that fewer than 6% of people discontinue their REM-modulating medications before undergoing an MSLT. The new protocol document includes a table of the most common drugs that may interfere with the MSLT.

“The AASM is making a bold statement on how to handle the appropriate taper for REM-modulating or alerting or sedating compounds,” says Cairns, who is head of sleep research at BioSerenity.

Among these compounds is marijuana, as tetrahydrocannabinol is known to have a profound effect on REM sleep, and stopping too close to the test may result in REM rebound. Compared to 2005, marijuana use for therapeutic purposes is much more common (with its legalization in a number of states).

MWT Protocol Changes

The maintenance of wakefulness test is infrequently used, but it may be ordered to provide information about the effectiveness of a treatment or to quantify daytime sleepiness for individuals who need to stay awake throughout the day. Unlike the MSLT, the MWT is not a diagnostic test.

The performance of a PSG before the MWT was reaffirmed as optional and left to the discretion of the sleep clinician. Although there are some cases that warrant a PSG prior to an MWT, the authors conclude typically it does not always inform the results of the MWT or impact its interpretation. But it is important the patient get adequate sleep quality and duration the night before the test so wakefulness can be accurately measured.

Another change to the MWT protocol relates to the test environment. Previously, during the test, patients were required to sit up in a bed surrounded by pillows to prevent injury. The task force recognized that a bed does not reflect a typical daytime setting and patients may be more comfortable sitting in a chair. Besides this, they found no evidence that sitting in a bed or sitting in a chair made any difference in the outcome. So the updated protocols include the ultimate consensus that either option could be used as long as it was used consistently for all the wake trials.

“It just seemed to make sense—if you wanted the MWT to reflect the probability that someone might fall asleep at an inappropriate time during the day, such as while driving or sitting at a desk or sitting at a computer,” Arand says.

Better Test Results

“Following the testing protocols and standardizing reporting will increase the value of the MSLT and MWT results,” says task force chair Lois Krahn, MD, professor of psychiatry at the Mayo Clinic in Arizona, in a release. Still, the authors remind clinicians that neither test should serve as the sole criterion for diagnosing hypersomnia or narcolepsy. Instead, the MSLT or MWT results are one piece of the puzzle that should be considered along with individual patient history and other relevant data.

Jane Kollmer is co-owner of Ch/At Communications, which provides writing and editing services to clients in the healthcare and travel industries.

Reference

Krahn LE, Arand DL, Avidan AY, et al. Recommended protocols for the Multiple Sleep Latency Test and Maintenance of Wakefulness Test in adults: guidance from the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. J Clin Sleep Med. 2021 Aug 23. Online ahead of print (scheduled to publish in the December 2021 print issue).

Illustration 5813640 © Willeecole | Dreamstime.com