An American Board of Dental Sleep Medicine diplomate explains why dentists who treat obstructive sleep apnea patients must be knowledgeable in temporomandibular joint dysfunction.

By Brock Rondeau, DDS, IBO, DABCP, D-ACSDD, DABDSM, DABCDSM

For many years, medical and dental clinicians have been debating the causes and treatment for temporomandibular (TM) dysfunction. Starting in 1936, Hans Selye, MD, of the International Institute of Stress, University of Montreal, Canada, wrote numerous articles and textbooks about the negative effects of stress on patients’ health. This had a profound effect on the medical profession’s view of this disorder, and many patients have told me their family doctors said their headaches and other symptoms were mainly psychological in origin. Another contributor to that conclusion is that many of these chronic pain patients suffer from depression. The medical profession responds with prescribing antidepressants, pain medication, muscle relaxants, and anti-inflammatory drugs. While they are beneficial to treat the symptoms, it would also be helpful to try to find the cause of the problem and treat it accordingly.

The dental profession holds the key to, and indeed the responsibility of, treating these patients. The medical profession is knowledgeable in treating all other joints in the body. It is the responsibility of the dental profession to treat the temporomandibular joint (jaw joint or TMJ).

Temporomandibular dysfunction (TMD) is extremely prevalent. The American Dental Association states that approximately 34% of the adult population has at least one sign or symptom of TMD. But this important disorder is not part of the curriculum in most medical and dental schools worldwide. Another problem is TMD is the “great imposter,” meaning so many of its signs and symptoms can mimic other disorders. (These include headaches, neck pain or stiffness, earaches, congestion or ringing in the ears, clicking, popping, or grating noises in the jaw joints when opening and closing the mouth, tired jaws or pain when chewing, limited mouth opening or jaw locking, dizziness and fainting, difficulty in swallowing, pain behind the eyes, numbness in the hands, and shoulder and back pain.) If dentists and medical doctors are not trained to recognize these patients and refer them to someone competent to treat them, then they will suffer endlessly.

Diagnosis of TM Dysfunction

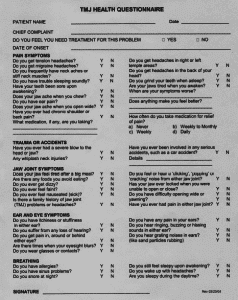

1. TMJ Health Questionnaire. Prior to any dental procedure, including oral appliance therapy for snoring and sleep apnea, every patient should be given a TMJ Health Questionnaire. It should ask numerous questions to see if they have any of the painful symptoms as outlined above. If the patient has numerous symptoms, then there is an increasing chance they may have TM dysfunction.

2. Range of Motion. If there are no structural problems within the TMJ, the patient should have normal range of motion (similar to other joints in the body).

The patient should be able to open approximately 50 mm, which means they should be able to fit three fingers in between the upper and lower front teeth when they open wide.

A normal movement laterally is 10 mm to 12 mm. If the patient cannot move laterally as described, this could indicate problems within the TMJ.

A normal protrusive movement is 8 mm to 10 mm. This is a particularly important movement if you are fabricating an oral appliance to prevent sleep apnea. The research clearly demonstrates that for oral appliances to be effective, the patient must be able to move the lower jaw forward. If the patient can only move the lower jaw forward 2 mm, then the oral appliance may not be effective.

Clinicians should ask the patient to open very slowly and evaluate the direction the mandible moves on opening. A normal movement opens straight. If the mandible deviates or deflects to one side, this usually indicates an internal derangement—a problem within the TMJ.

3. Intracapsular. Intracapsular problems are problems within the TMJ. The clinical signs are clicking and popping noises within the joint when the patient opens and closes. A normal TMJ is noiseless and painless.

4. Extracapsular. Extracapsular problems are basically muscle-related problems outside the TMJ. This is evidenced by the muscles of mastication being extremely sore, especially in the morning when the patient clenches or bruxes at night.

5. Muscle Palpations. It is important for clinicians to palpate the head and neck muscles to determine if the muscles are sore due to excessive contractions. Sore muscles indicate a TMJ problem. When the lower jaw (mandible) is not in the correct position to the upper jaw (maxilla) either anterio-posteriorly, transversely, or vertically, then the muscles of the head and neck often become sore upon palpation.

If the patient wakes up with headaches, this is often indicative of clenching or bruxing all night.

Treatment of TM Dysfunction

1. Internal Derangement of TMJ (Intracapsular). The clinical signs would be clicking or popping noises when the patient opens and closes. The cause is an anteriorly displaced disc. When the patient opens, the condyle moves forward on to the anteriorly displaced disc causing the clicking noise. The cause of the problem is that the lower jaw is located too far back when the patient bites on the back teeth. The solution is to use a lower repositioning indexed splint to be worn during the daytime to move the lower jaw forward. When the click is eliminated when the patient opens and closes in the new forward position, this eliminates over 94% of the TMJ symptoms.1

Patients with internal derangements wearing oral appliances for snoring and sleep apnea often wake up with posterior open bites in the morning. Patients must be advised this is a possible side effect of wearing oral appliances that move the lower jaw forward in order to open the airway. In most cases, the patient’s bite will return to normal after approximately 30 minutes. However, in severe cases, the patient will be left with an open bite between the posterior teeth. Most patients will accept a bad bite in return for wearing the oral appliance that successfully treated the snoring and sleep apnea. One possible solution is for the patient to wear an anterior repositioning splint during the daytime to allow for proper chewing, and an oral appliance at night to prevent the snoring and sleep apnea. Although this posterior open bite is rare, patients must be advised as to the possibility (especially if they have an internal derangement) prior to oral appliance therapy.

Classifications of Internal Derangements/Summary of TMJ Treatment

Stage 1: Jaw clicking, no pain

No treatment

Stage 2: Jaw clicking, intermittent locking, pain

Daytime lower repositioning splint

Nighttime upper anterior deprogrammer

Stage 3: Chronic closed lock, pain

Distraction appliance or surgery

Refer to TMJ specialist

Stage 4: Early degenerative osteoarthritis, pain

Same treatment as Stage 2

Stage 5: Advanced degenerative osteoarthritis

Crepitus, pain

Refer to TMJ specialist

2. External Derangement (Extracapsular). Extracapsular problems can be caused by occlusal interferences or parafunctional habits such as clenching or bruxing. The solution is to wear an upper appliance called an anterior deprogrammer at night to help eliminate the parafunctional habits. The anterior deprogrammer has an anterior bite plate that contacts only with the lower central and lateral incisors. This prevents the posterior teeth from occluding. When the posterior teeth are unable to contact, the temporalis and masseter muscles are unable to contract excessively. This helps prevent the clenching and grinding at night as well as the headaches upon awakening.

3. Upper Flat Plane Splints (Mouthguards). The most popular splint used worldwide to prevent TM dysfunction is the upper nightguard.2 This is a flat plane splint that allows contact with the lower posterior teeth.

a) External Derangement (Extracapsular): Research has shown that the upper nightguard not only does not prevent bruxism but makes it worse.3 To eliminate bruxism, you must prevent the posterior teeth from contacting during swallowing.

b) Internal Derangement (Clicking Jaw): When a patient wears a flat plane upper nightguard, the lower jaw goes posteriorly. Patients with clicking jaws already have their jaws posteriorly displaced with the disc anteriorly displaced. Therefore, flat plane nightguards do not solve the problem. Even worse, patients in Stage 2 internal derangement (clicking jaw) can often end up with Stage 3 internal derangement (lock jaw).

c) Aggravation of Respiratory Disturbances by Use of Flat Plane Occlusal Splints (Nightguards) in Apneic Patients: The problem is the upper flat nightguard causes the lower jaw to go back and the tongue to go back, which blocks the airway at night. The result is illustrated in an article published in the International Journal of Prosthodontics. Snoring increased 40% using this upper nightguard, and AHI increased more than 50% in 5 out of 10 patients.4 Clearly, it is not advisable to use upper flat plane maxillary splints in patients who snore or have sleep apnea.

Sadly, this flat plane upper occlusal splint is the most popular one that is taught in dental schools around the world.

Conclusion

If 34% of the population has TMJ dysfunction and the medical and dental schools are not effectively teaching their graduates to either diagnose or treat it, this is a major problem for the

public. Dentists need to stop fabricating upper nightguards (flat plane occlusal splints) for patients whose jaws click on opening, who brux at night, or who snore or have sleep apnea. It is time for the dental profession, particularly the dentists fabricating oral appliances, to become more knowledgeable in the diagnosis and treatment of patients with TM dysfunction to help improve the health of our patients.

Brock Rondeau, DDS, IBO, DABCP, D-ACSDD, DABDSM, DABCDSM, is a diplomate of the American Board of Dental Sleep Medicine. He is the owner of Rondeau Seminars, which provides dental continuing education. View the class schedule at www.rondeauseminars.com.

REFERENCES

1. Simmons HC 3rd, Gibbs SJ. Recapture of the temporomandibular joint disks using anterior repositioning appliances: an MRI study. Cranio. 1995;13(4):227-237.

2. Pierce CJ, Weyant RJ, Block HM, Nemir DC. Dental splint prescription patterns: a survey. J Am Dent Assoc. 1995;126(3):294.

3. Holmgren K, Sheikholeslam A, Rüse C. Effect of a full-arch maxillary occlusal splint on parafunctional activity during sleep in patients with nocturnal bruxism and signs and symptoms of craniomandibular disorders. J Prosthet Dent. 1993;69:293-297.

4. Yves G, Pierre M, Gilles L. Aggravation of respiratory disturbances by the use of an occlusal splint in apneic patients: a pilot study. International Journal of Prosthodontics. 2004;17:447-453.

Brock, you did an excellent job on this article! It is clear, factual, readable, and important. I will certainly pass it around.

Very well said Brock. This should be “ear”-opening for many dentists,physicians and patients who don’t clearly understand OSA, TMD and the interrelationship.

Great summary!