Age-associated changes in the activity of neurons, a group of brain cells that transmit information, are responsible for disrupted sleep in older mice, according to a study published in Science.

As mice age, the neurons that control wakefulness become hyperactive, leading to fragmented, poor-quality sleep. Drugs that reduce neuron activity help improve sleep, suggesting a potential strategy to improve sleep quality in older adults, the research suggests.

Poor sleep is one of the most common health complaints of older adults, many of whom wake up frequently at night, which can impact their ability to function during the day. Problems staying asleep during aging occur across species, but the mechanism behind these sleep disruptions is poorly understood. A team of researchers at Stanford University’s Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill have added to this body of knowledge by finding that neurons that promote wakefulness become hyperactive with age, leading to poor sleep.

A specific set of brain cells, called hypocretin (Hcrt), secrete neurons that play a central role in controlling sleep and wakefulness. Activating Hcrt neurons can wake sleeping mice and suppressing Hcrt neuron activity can cause mice to fall asleep. Based on these observations, scientists believe Hcrt neuron activity promotes wakefulness.

Members of the research team hypothesized that overactive Hcrt neurons could drive age-related changes in sleep quality. Results showed that although mice lost Hcrt neurons as they aged, the cells that remained were hyperactive and overly sensitive to stimulation, causing sleep problems.

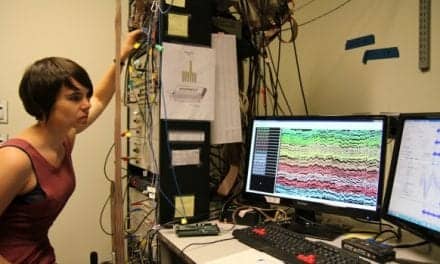

The researchers used genetic techniques to place a molecular switch in mouse Hcrt neurons that could be controlled with light. In this system, exposing a sleeping mouse to blue light activates Hcrt neurons and awakens the mouse. During the study, researchers found that aged mice responded more dramatically than young mice to blue light, causing longer periods of wakefulness.

The scientists determined the increased sensitivity of Hcrt neurons in aging mice resulted from the loss of KCNQ2 potassium channels — proteins that control how neurons respond to a stimulus. These results suggest that as mice age, they lose KCNQ2 activity in Hcrt neurons, making them overactive, and causing fragmented sleep. Using drugs to increase KCNQ2 channel activity restored Hcrt neuron sensitivity to normal and improved sleep quality in aged mice.

Because neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s often cause sleep disruptions, future studies will focus on how Hcrt neurons behave in brains with this disease. Previous studies have shown that amyloid beta — a protein that builds up in Alzheimer’s — can cause mouse neurons grown in petri dishes to lose KCNQ2 potassium channels. Using this information, scientists may study whether targeting overactive Hcrt neurons could be a way to improve sleep in older adults with and without Alzheimer’s.