Richard B. Berry, MD, Excellence in Education Award recipient, inspires students to follow his lead in delivering top-notch patient care.

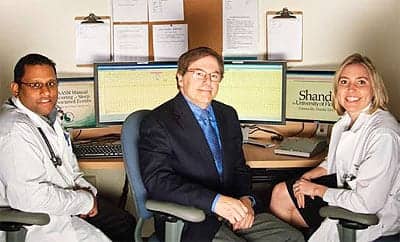

Richard B. Berry, MD, center, Ashish Prasad, MD, left, and Klark Turpen, MD, right, collaborate on a patient treatment plan. Berry actively challenges colleagues to continue advancing their knowledge of sleep medicine. Photos by Tim Healy

By Julie Ross and Alison Werner | Photography by Tim Healy

The lay person may take for granted the difference a good night’s sleep can make in their life or in their health, but for Richard B. Berry, MD, professor of medicine in the Division of Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine at the University of Florida and medical director of the UF & Shands Sleep Disorders Center, it was one of the main reasons he entered the sleep medicine field.

“I thought sleep medicine was interesting because you can make such a difference in patients’ lives by improving the quality of their sleep,” says Berry. And while his decision to enter the field of sleep medicine has certainly had an impact on both his patients’ sleep and their lives, it has had a ripple effect—affecting the lives of every student and the sleep quality of every one of their patients for the better.

THE AWARD

In June, Berry was awarded the American Academy of Sleep Medicine’s 2010 Excellence in Education Award. The award is presented to an individual who has made outstanding contributions in the field of teaching sleep medicine. Berry, who served on the AASM board of directors from 2005 to 2008, has been a leader in the AASM’s initiatives to provide educational opportunities for sleep medicine professionals.

“Dr Berry is recognized as one of the leading educators in the field of sleep medicine,” says Patrick J. Strollo, Jr, MD, FCCP, current president of the AASM. “His commitment and dedication to the education of health care professionals has helped the AASM promote excellence in the provision of sleep-related medical care.”

WAKING TO SLEEP

When Berry initially entered the medical field after completing his medical degree at UF in 1978 and his residency in internal medicine at the University of California, Irvine, in 1981, he hadn’t envisioned a career in sleep medicine. It wasn’t until he returned to UF in 1982 to complete a fellowship in pulmonary medicine that his interest was piqued. There, he met the late A. Jay Block, MD, FCCP, chief of the Pulmonary and Critical Care Division from 1970 to 1998 and a pioneer in sleep medicine.

“Jay, to whom I owe a lot for getting me interested in and pushing me toward sleep medicine, started talking to me about a research project he was doing on CPAP,” recalls Berry. “I was just fascinated, but I knew nothing about sleep. So, Jay sent me to the laboratory of Dr Wilse Webb (another pioneer in sleep medicine at UF) to learn how to perform sleep studies—beginning with how to put the electrodes on patients. Pretty soon, I started experimenting with technology—for example, constructing a makeshift CPAP machine with a nasal mask made out of an anesthesia mask, because at the time, there were no commercial CPAP units.” Eventually Berry learned how to operate a polygraph and perform sleep studies by himself. He and Block completed a study on snoring and CPAP use that eventually was published in 1984 in the journal Chest. The first night his makeshift CPAP device converted “wall shaking snoring” to peaceful sleep, as Berry puts it, he was “hooked.”

While Berry went into private practice for a year after his fellowship and time with Block at UF ended, he soon returned to the sleep medicine field to continue the work he had started with his mentor. Berry returned to UC Irvine and the Long Beach VA Medical Center (an affiliate of UC Irvine) and went to work to create a sleep medicine niche within the pulmonary department at UCI. In addition, he persuaded the powers-that-be at the VA Medical Center to set up a sleep lab there.

While integrating sleep and pulmonary disciplines at UC Irvine/Long Beach VAMC, Berry sought to expand his own perspective and turned to Jon Sassin, MD, a neurologist and sleep expert at UC Irvine Medical Center at the time, to learn everything he could about the nonpulmonary aspects of sleep medicine. “I owe Dr Sassin a great deal for his help in broadening my knowledge. At that time, he was one of the few individuals at UC Irvine who shared my excitement about sleep medicine,” says Berry. “I still remember being told by a senior pulmonary physician in 1983 that CPAP really doesn’t work.” Berry committed himself to a multidisciplinary approach to sleep medicine that has made the field richer and his former students better practitioners. Later, Michael Bonnet, PhD, joined the VA and also helped Berry widen his knowledge about sleep medicine and sleep research. With his help, Berry became certified in sleep medicine in 1989 (then called “accredited clinical polysomnographer”).

Richard B. Berry, MD, supports a multi-

disciplinary approach to sleep medicine

for patients like Dylan Moquin.

STEPPING TO THE HEAD OF THE CLASS

Although the Long Beach VA had a “nice” sleep program and was a “great” place to do sleep research, according to Berry, he felt stifled by the fact that the UC Irvine sleep center was not itself multidisciplinary and that he was not permitted to fully participate in the university’s sleep program. Ultimately, Berry found himself returning to his alma mater in 1999 to continue his development as a sleep professional and to share his interest in sleep medicine with future sleep medicine professionals in adult and pediatric neurology and pediatric pulmonary.

Berry returned to UF, this time as medical director of the University Sleep Center and the Malcom Randall VA Medical Center’s sleep medicine program. From 1999 to 2010, UF & Shands Sleep Disorders Center grew from two to 10 beds and from performing 250 sleep studies yearly to more than 2,700 and earning AASM accreditation. The VA sleep program now is also one of the largest in the country. At UF, he delved into education more fully and began to make a wider impact as a teacher.

“I got involved in sleep education because I enjoy teaching,” says Berry. “When you teach, you always learn many things yourself.”

At UF, Berry’s commitment to the education of future sleep practitioners led him to establish an accredited sleep medicine fellowship at the University of Florida. The program is structured along Berry’s belief that a multidisciplinary, interactive, case-based education is the best way for students to learn. Fellows are also encouraged to become involved in either basic or clinical research involving sleep disorders during their time in the program.

During his tenure at UF, Berry has also ensured that his commitment to a multidisciplinary approach to sleep medicine has been instilled in the department. “Some programs are still controlled by one speciality, but those days are coming to an end,” says Berry, as those in the field increasingly recognize the contributions different specialties can make to sleep cases. “I was so frustrated that I could not be included in the sleep center at UC Irvine that when I came to Florida, I vowed to make it a multidisciplinary program. At first, some of my pulmonary coworkers would say things like, ‘Neurologists should not take care of patients with sleep apnea.’ I told them I didn’t want to hear that kind of talk.”

Abby Wagner, MD, codirector of the UF Sleep Medicine Fellowship and pediatric medical director of the university’s sleep laboratory, applauds Berry’s drive to create such a program at UF, adding that it says a lot about his commitment to advancing the field and ensuring the best education for future sleep physicians.

“The fact that our sleep program is multidisciplinary—covering neurology, pediatric pulmonary, ENT surgery, and adult pulmonary—and that under [Richard], UF’s Pulmonary and Critical Care Division became the Pulmonary, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine Division, speaks volumes about him as an educator and about his dedication to bringing more physicians into the field, as well as broadening education to take into account every area that has an impact on sleep,” says Wagner. “This isn’t something that can be said of your average sleep specialist.”

For former student Prakash Patel, MD, FCCP, of Smyrna Pulmonary and Sleep Associates in Smyrna, Tenn, Berry’s multidisciplinary approach has made Patel better able to serve his patients. Whether it be a pediatric patient or a patient with sleep apnea who needs a referral to an ENT for further treatment, Patel says his time training under Berry at UF and Berry’s insistence that he train among different subspecialties have made him better able to serve his patients. “I know more what they need and what to look for,” says Patel.

According to Wagner, Berry also makes a point of ensuring his colleagues at UF keep abreast of the latest in the field. “While my specialty is pediatrics, Richard is always making sure that I am on track in advancing my knowledge of sleep medicine beyond that field.”

PEARLS OF WISDOM

Berry’s commitment to advancing the sleep field and best educating its practitioners has extended beyond directly training students. Looking to spark the interest of more physicians and fellows in the field of sleep medicine, he set out to write a book that would translate his teaching philosophy onto the printed page and hopefully attract more people to the field and educate them.

“There were a number of [sleep medicine] texts available, but they tended to be large encyclopedias filled with dazzling EEG terminology or slices of rat brains,” says Berry. “I thought a more practical book was needed, particularly because in my opinion and experience, people learn far better from an interactive, case-based approach than from lecturers and straight from text.”

Despite seeing a place for such a text in the literature, Berry was discouraged when neither the publisher nor the Pearls series editors initially embraced his idea. David P. White, MD, clinical professor of sleep medicine at Harvard Medical School, and collaborator with Berry on several sleep studies, intervened, encouraging Berry to remain committed to the project and advising the publisher to take on the title.

Richard B. Berry, MD, was presented the 2010 American Academy of Sleep Medicine Excellence in Education Award. He has been a leader in the AASM’s initiatives to provide educational opportunities for sleep professionals.

“I talked him back into it,” says White, who is also senior physician in the Division of Sleep Medicine in the Department of Medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston. “Not only did I think it would be good for his career, and that the field of sleep medicine needed a book akin to the other Pearls books to complement the intricate texts out there, I was convinced that his innate ability to explain relatively complex physical concepts in an engaging way [would produce a good book].”

In 1999, Sleep Medicine Pearls was published. (The second edition was released in 2003.) Unlike other texts in the Pearls series, Sleep Medicine Pearls took on a different format to allow for the inclusion of fundamentals of the field section.

“I arranged the book so someone without any knowledge of sleep physiology or technology would, after finishing it, possess the most important core of knowledge needed to practice sleep medicine,” says Berry.

Richard Rosenberg, PhD, ABSM, director of professional education and training at the AASM, agrees. “I think one thing Rich has done is make his textbooks very well written and engaging. I think that broadens the audience that [can learn] the basics of sleep medicine. Translating the sleep medicine specialty [material] into something that nonspecialists can understand has been one of his strengths.

“There are a lot of people who swear by his clinical pearls book as being one of the best introductions to sleep medicine,” adds Rosenberg.

To this day, Berry considers the publication of Sleep Medicine Pearls his most significant contribution to sleep medicine. “Physicians have told me they decided to go into sleep medicine or passed their boards because of the book.” He finds that fact “especially gratifying, as the field needs more dedicated professionals.”

THE EDUCATOR

Still, it is as a course instructor, or one-on-one with future sleep physicians, that Berry might have the most lasting impact.

“He’s an excellent educator,” says Patel, who had Berry as his mentor for his sleep training while doing a pulmonary fellowship at UF. “He’s a hard-working, easy-going teacher. He was always there when I had a question or concern. I didn’t know I wanted to do sleep, but I started training with him, and that’s why I decided that [sleep] might be something to go into.”

Away from UF, Berry, who served as a past president of the American Sleep Medicine Foundation, the foundation of the AASM, has been especially involved in the association’s education programs, chairing its National Sleep Medicine course from 2003 to 2005, and serving as a faculty member on many postgraduate courses at the annual SLEEP meeting from 2006 to 2009. More recently, he taught the interpreting sleep studies courses.

“Rich doesn’t provide black-and-white answers. He gives [students] a lot of background and rationale and the thinking that went into the decisions. He presents both sides of the argument very well and really gets to the critical meat of the problems of interpreting sleep studies in his lectures,” says Rosenberg.

When students leave a Berry lecture, Rosenberg adds, they go home thinking. “He’s not the kind of guy where he gives you fact A, fact B, fact C and you memorize it. He’s very provocative in terms of getting people to think about what they’re doing. He’s one of the guys where he gives a talk, and then at the end, half the audience swarms up to the front to ask him a question about something.”

Wagner agrees, noting that Berry’s “educator persona” has been key to both the success of UF’s sleep fellowship and the expansion of the university’s sleep laboratory over the last decade.

“[Berry] is very good at cutting to the chase in conveying information, as well as explaining concepts, so that they are easily understood, even if one isn’t a sleep physician or a neuroscientist,” says Wagner. “Just as importantly, he is driven to help sleep medicine succeed and to foster the development of knowledge by fellows or anyone who studies with him in any capacity.”

Julie Ross is a freelance writer based in New Jersey. Alison Werner is associate editor for Sleep Review.