In response to a Sleep Review article, sleep physicians and dentists raise concerns about whether and, if so, how to incorporate home sleep apnea testing into oral appliance therapy.

The article written by Anthony Dioguardi, DMD, titled “Incorporating Home Sleep Testing into Oral Appliance Therapy,” published online on sleepreviewmag.com on July 4, 2016, and in the July/August 2016 print issue of Sleep Review, is well written but raises concerns. We are sharing our concerns for the benefit of sleep physicians, qualified dentists interested in oral appliance therapy (OAT), and especially patients with obstructive sleep apnea (OSA).1

The 2013 American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine (AADSM) treatment protocol states, “the dentist may obtain objective data during an initial trial period to verify that the oral appliance effectively improves upper airway patency during sleep,” and does not specify the device to be used to obtain objective data, or how the data should be obtained.2

The 2015 Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of OSA and Snoring with Oral Appliance Therapy, which was developed jointly by the AADSM and the American Academy of Sleep Medicine (AASM), states in recommendation 4.2.d: “We suggest that sleep physicians conduct follow-up sleep testing to improve or confirm treatment efficacy, rather than conduct follow-up without testing, for patients fitted with oral appliances.”3 This recommendation was based on randomized controlled trials and on studies using in-lab polysomnograms (PSGs), and only in one single report, a 7-channel unattended test that recorded chest and abdominal movement, oxygen saturation, oro-nasal airflow, heart rate, body position, and parapharyngeal noise.4 There were even less sufficient data on other objective tests such as the 4-channel home sleep apnea tests (HSATs) or overnight oximetry studies. As these studies on research subjects were conducted by and reviewed by sleep physicians—and not by dentists—the recommendation specifically states that sleep physicians conduct follow-up testing on these patients.

Moreover, use of multiple HSATs to “titrate” oral appliances is not backed by the current clinical practice guideline. It has been shown that there is greater success when an oral appliance is adjusted with PSG.5 Furthermore, the cost-effectiveness of using multiple HSATs is unknown and may increase financial burden for patients. Dentists’ use of HSATs to assess the efficacy of oral appliances would amount to assessment of a residual medical condition (that is, OSA).

We therefore recommend to readers that they:

a. Follow the recommendations in the current 2015 clinical practice guideline paper on oral appliance therapy.3

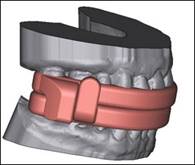

b. Establish active collaboration between sleep physicians and qualified dentists6 to manage OSA patients with oral appliances, with clearly defined roles based on current guidelines and evidence: 1) sleep physicians take responsibility for diagnosis, treatment, prescription, interpretation of sleep studies and objective data, and long-term management of OSA; 2) qualified dentists take responsibility for fitting and delivery of an appropriate, titratable oral appliance; adjusting the appliance to optimize effectiveness in a mutually agreed upon protocol with the sleep physician; and managing dental-related side effects.

The authors were members of the task force that developed and wrote “Clinical Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Obstructive Sleep Apnea and Snoring with Oral Appliance Therapy: An Update for 2015,” which was published jointly by the American Academy of Sleep Medicine and American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine.

Reply to: Recommendations for Oral Appliance Therapy Collaboration to Treat Obstructive Sleep Apnea

Thank you for your thoughtful letter about the role of qualified dentists in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea. As the author of the July/August 2016 Sleep Review article, I appreciate the dialogue on the ongoing effort for physicians and dentists to collaborate to treat OSA.

In your letter, you refer to the 2013 AADSM treatment protocol, which states, “the dentist may obtain objective data during an initial trial period to verify that the oral appliance effectively improves upper airway patency during sleep.” Since the protocol does not specify how this objective data is gathered by the dentist, it follows that a computer-scored HSAT is one way that could be used.

You correctly assert that the guideline does not specify the device to be used to obtain objective data, or how the data should be obtained. As such, I believe that more specific published guidelines regarding the use of rapidly evolving HSAT technology in the dental setting will be of great value in promoting effective collaboration between the professions.

I agree the responsibility for the confirmation of treatment efficacy lies solely with the sleep physician. Indeed, the article described an attempt to use current technology to enable the dentist to more effectively adjust the appliance before the patient returned to the sleep physician for re-evaluation.

You also correctly note that the “use of multiple HSATs to ‘titrate’ oral appliances is not backed by the current clinical practice guideline.” I believe the gathering of objective data from multiple HSATs as described in my article, although not specifically described, is consistent with the current AADSM guidelines.

In my article, I implied but should have clarified that there neither was, nor should there be, any additional fee for these computer-scored HSATs. If HSAT technology enables a dentist to more accurately and efficiently estimate a therapeutic appliance setting during the initial adjustment period, it has the potential to reduce the number of visits and tests necessary for the physician to evaluate efficacy and thereby result in lower financial burden for patients.

Finally, I agree that “it has been shown that there is greater success when an oral appliance is adjusted with PSG.” Unfortunately, this option is often not available to patients in the real-world scenario where PSGs are denied by insurance companies in favor of the far less expensive physician-ordered HSATs. Some insurance companies pay for only one test in a patient’s lifetime.

As technology and healthcare delivery systems rapidly evolve, I welcome continued guidance by our professional organizations, which support all our efforts to best serve our patients.

The author is a general dentist with extensive training and experience in the management of snoring and obstructive sleep apnea with oral appliances. As an active participant with Yale University’s Sleep Medicine post-doctorate fellowship program since 2009, he provides clinical and academic instruction in the dental treatment of sleep-disordered breathing. He is a member of Sleep Review’s editorial advisory board.

[sidebar]

Recommendations for Terminology for Home Sleep Apnea Testing

The authors of “Recommendations for Oral Appliance Therapy Collaboration to Treat Obstructive Sleep Apnea” note that the AASM now recommends use of the term “home sleep apnea test” (HSAT) for devices that patients use at their homes or outside the sleep center without a technician monitoring the study.7 This term is preferable to home sleep testing (HST, as used in Sleep Review), as these tests do not usually monitor sleep. Other older terms such as portable sleep tests, or out of center sleep testing (OCST), have similar potential to be misleading.

Sleep Review reply to: “Recommendations for Terminology for Home Sleep Apnea Testing”

The AASM updated its AASM Style Guide for Sleep Medicine Terminology (available online: www.aasmnet.org/ebooks/terminologystyleguide/flippingbook/#1 ) to recommend the use of “home sleep apnea testing” in November 2015. Sleep Review became aware of this change in June 2016.

Sleep Review is an independent trade publication with our own style guide, separate from that of any academies or associations. But, of course, we too periodically reevaluate our terminology. And upon learning about the AASM’s terminology change, we took the opportunity to determine if we should change to “HSAT” as well.

We ultimately decided to continue using our current terminology of “home sleep test (HST).” HST is a well-known acronym that most healthcare professionals recognize. We want to continue to educate a comprehensive audience (not all of whom are AASM members) and found that much of our audience arrives at sleepreviewmag.com via Google using common terms like “HST.” As such, we do not want to jeopardize our educational reach by using a new term that is not currently well known or used consistently. For our writers who feel strongly that their articles use the term “HSAT,” we will, however, accommodate them.

Finally, as the AASM noted, the terminology for this type of test has already evolved several times. At Sleep Review, we suspect it may continue to evolve in the near term due to advances both in the technology and in the location of the tests (for example, home sleep tests are not necessarily conducted in a “home”). We will continue to reevaluate our terminology moving forward. You are welcome to weigh in on the debate: E-mail me at sroy[at]allied360.com.

References for Recommendations for Oral Appliance Therapy Collaboration to Treat Obstructive Sleep Apnea & Recommendations for Terminology for Home Sleep Apnea Testing

1. Dioguardi AT. Incorporating home sleep testing into oral appliance therapy. Sleep Review. 2016 July 4. Available from: https://sleepreviewmag.com/2016/07/home-sleep-testing-oral-appliance-therapy.

2. American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine. AADSM treatment protocol: oral appliance therapy for sleep disordered breathing: an update for 2013. June 2013. Available from: http://aadsm.org/treatmentprotocol.aspx.

3. Ramar K, Dort LC, Katz SG, et al. Clinical practice guideline for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea and snoring with oral appliance therapy: an update for 2015. J Clin Sleep Med. 2015;11(7):773–827. Available from: http://www.aasmnet.org/Resources/clinicalguidelines/Oral_appliance-OSA.pdf.

4. Rose E, Staats R, Virchow C, Jonas IE. A comparative study of two mandibular advancement appliances for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnoea. Eur J Orthod. 2002;24(2):191-8. Available from: http://ejo.oxfordjournals.org/content/eortho/24/2/191.full.pdf.

5. Gagnadoux F, Fleury B, Vielle B, et al. Titrated mandibular advancement versus positive airway pressure for sleep apnoea. Eur Respir J. 2009;34(4):914-20. Available from: http://erj.ersjournals.com/content/34/4/914.long.

6. American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine. Qualified dentist designation. Darien, IL: American Academy of Dental Sleep Medicine; c2016 [cited 2016 Sep 28]. Available from: http://aadsm.org/dentistqualified.aspx.

7. American Academy of Sleep Medicine. AASM style guide for sleep medicine terminology. Updated November 2015. Darien, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine; 2016. Available from: http://www.aasmnet.org/library/default.aspx?id=15.