Why are only about 50% of obstructive sleep apnea patients CPAP adherent? New data spurs some sleep specialists to look differently at positive airway pressure flow profiles—and suggest pressure relief might be best placed where we least expect it.

By Chaunie Brusie, RN, BSN

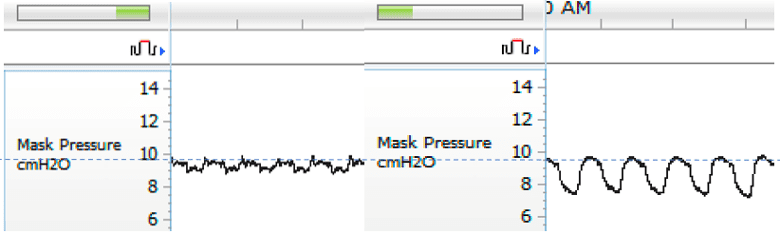

For the past two decades, CPAP devices have been designed to maintain inspiratory pressure—the pressure level when a patient inhales—for the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea.

Technical improvements, such as increasingly faster-to-adjust turbines within CPAPs, have made maintaining inspiratory pressure even more seamless. Patients who express trouble with their pressure settings have their CPAP expiratory pressure dropped—a lessening of the pressure level during exhalation—via an expiratory pressure relief feature available on many of today’s devices or a ramp feature, which drops both inspiratory and expiratory pressure together for about 30 minutes before gradually increasing both to the prescribed pressure.

The assumption with these strategies is that upper airway obstruction is primarily an inspiratory problem, likely enhanced by negative intraluminal pressure collapsing forces in those with inherent structural instability.

Inspiratory pressure is, in fact, key for patients who cannot breathe on their own, which is the case for critical care patients who need true ventilation therapies, says Eugene Scarberry, a retired long-time engineer for Respironics (now Philips Respironics). Scarberry was the correspondent contact for the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) submission for Respironics’ first nasal CPAP device in 1984, which he helped develop and which received FDA clearance that same year. Many CPAP makers assume that offering inspiratory pressure for CPAP users would reduce their work of breathing as well, making CPAP use more comfortable, Scarberry says, noting that he contributed to this assumption when developing bilevel PAP therapy in the mid-1980s.

But now, after a review of 40 years of peer-reviewed literature sparked by his knowledge of recent yet-to-be published clinical trials, Scarberry has changed his mind about positive airway pressure flow profiles.

“In the early days, we were dealing with pulmonologists coming over who are familiar with critical care, and they saw this treatment as another way of ventilating patients,” Scarberry says. “And in retrospect, we made a mistake.”

A New (Old) Theory About CPAP Pressures

Today’s positive airway pressure devices for obstructive sleep apnea therapy offer relief from the air pressure during expiratory pressure. But Scarberry is not the only long-time sleep medicine stakeholder who now thinks that modern positive airway pressure device algorithms have it wrong.

Expiratory pressure, they say, is key to successful therapy and should not be lessened, while inspiratory pressure could be lessened for most patients without loss of efficacy. With a few exceptions, such as for patients who also have COPD or hypoventilation, inspiratory pressure relief would increase comfort while still fully treating the obstructive sleep apnea.

In other words, today’s machines have it backwards. But where did this theory come from, and where is it being tested?

Though it sounds counterintuitive, the perspective that a lower inspiratory positive airway pressure (IPAP) and higher expiratory positive airway pressure (EPAP) can treat obstructive sleep apnea is not actually new.

“As CPAP adherence is stuck in the mid 50% or so at two years of use, we need to look back at the trajectory of CPAP development to move forward,” says pulmonologist-sleep specialist Kingman P. Strohl, MD, a professor of medicine at Case Western Reserve University.

Strohl looks back to his own sleep research from 1986, in which he and a co-investigator conducted a study using first-generation Respironics CPAPs in which patients were successfully treated with no airway closure.1 The catch? First- and second-generation CPAPs had inspiratory pressure as lower than expiratory pressure—almost a third of the expiratory pressure, Strohl says, because older technology with slower-adjusting blowers meant these devices were unable to maintain prescribed pressure as the patient breathed in. The inspiratory pressure drop, though inadvertent, seems meaningful to Strohl now. It “can feel more natural” for IPAP to be less than EPAP, he says, which could potentially lead to increased adherence.

Pulmonologist-sleep specialist Robert J. Farney, MD, who co-established Intermountain Sleep Disorders Center for Intermountain Healthcare in 1983, also had his interest in modifying inspiratory pressure sparked recently.

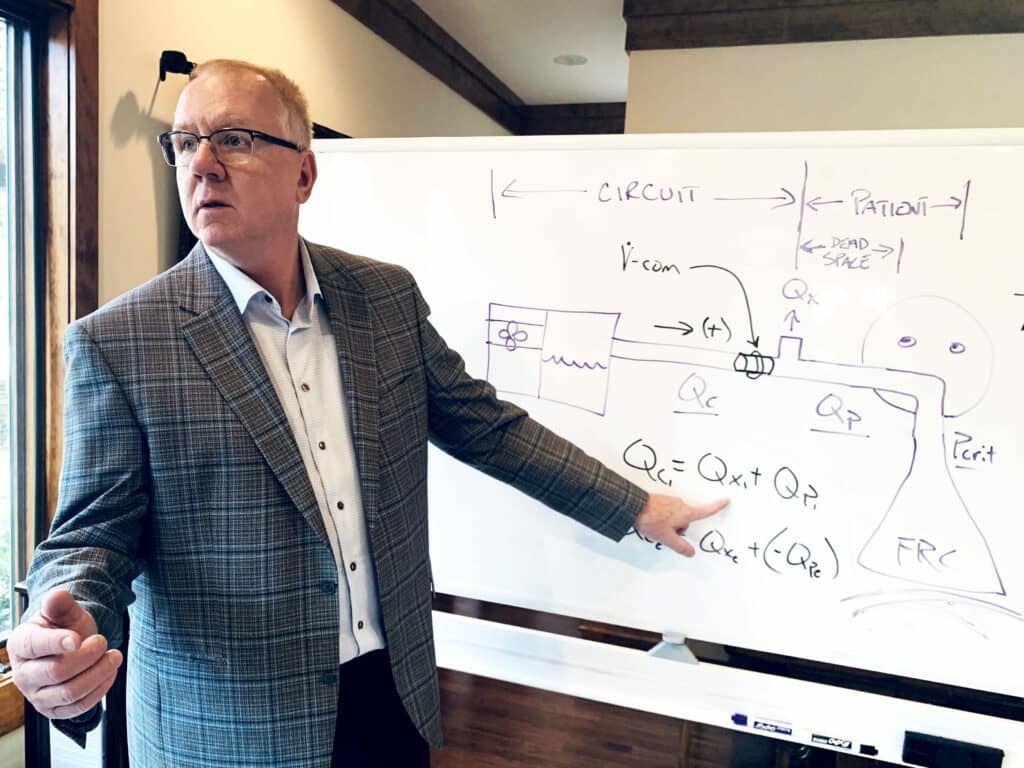

The University of Utah professor of medicine was contacted by sleep specialist William H. Noah, MD, a former pulmonary fellow at the university, to review data Noah collected from a CPAP accessory he developed, named V-Com, that would lower inspiratory pressure only.

Download data from 101 patients shows that the V-Com reduced IPAP, reduced leak, and maintained effective therapy based on the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), says Farney, who has not received any money from V-Com development or its parent company SleepRes LLC. He says, “I have investigated a small number of patients with and without the V-Com device using unattended cardiopulmonary sleep studies and have not observed any adverse consequences of PAP efficacy. I have found reduced leak and better comfort but my own experience at this point is anecdotal and quite limited by numbers.” The University of Utah Sleep Wake Center plans to collaborate with Noah to extend this research.

For now, Farney says a review of V-Com data and of peer-reviewed research about first- and second-generation CPAP devices has made him rethink obstructive sleep apnea therapy. “The most critical moment occurs as expiration is terminating at which time the airway diameter is becoming smaller and at functional residual capacity (FRC) when the airway is the smallest,” he says.

“Maintaining positive airway pressure towards the end of expiration (EPAP) is most critical for preventing closure and low EPAP is not offset by very high IPAP. In fact, low IPAP does not appear to be an important factor in reversing airway obstruction.”

Testing Lower Inspiratory Pressures

Noah, medical director of Sleep Centers of Middle Tennessee PLLC and CEO of SleepRes, started conducting his own research on CPAP pressures while holed up in his basement sleep research lab during the pandemic. After researching how the original CPAP designs worked primarily with expiratory pressure instead of inspiratory pressure, he got to work developing a prototype accessory he could use on his own CPAP to make it more comfortable to use.

Some of the literature he found most compelling for the theory of the leading role of expiratory pressure in CPAP therapy include:

- a paper from 1983 that found a focus on positive expiratory pressure reduced the frequency and duration of apneas and the degree of nocturnal oxygen desaturation and improved sleep quality in patients with obstructive sleep apnea;2

- a paper from 1992 that performed awake computed tomography on eight patients with obstructive sleep apnea and found 12 cmH2O during both inspiration and expiration to be more effective in splinting the airway open than 12 cmH2O during inspiration and only 6 cmH2O during expiration;3

- a paper from 1999 that found “OSA is not an ‘inspiratory’ problem…but an expiratory-inspiratory phenomenon…Indeed, we have shown that if a sufficiently high pressure is not applied during expiration, the patient is unable to trigger inspiratory airflow during the following inspiration even in the presence of high inspiratory pressure.”4

With this research in mind, Noah designed a prototype and had it 3D-printed at a local university. He began testing it on himself and a few friends and confirmed the accessory didn’t change his therapy, didn’t add any events, and was more comfortable than traditional CPAP use. “I’ll be honest with you—it was hard to believe,” Noah says.

After getting FDA clearance for V-Com as a comfort accessory, Noah started testing it on patients who were willing to try it when starting on CPAP. For the occasional obstructive sleep apnea patient who also has poor lung or chest wall compliance (for whom inspiratory pressure is needed to relieve the work of breathing), Noah says these patients can still use the V̇-Com for a softer inspiratory flow profile, as long he then adjusts the IPAP upward to ensure adequate tidal volumes. For the more than 90% of obstructive sleep apnea patients he sees who have fair to normal lung or chest wall compliance, he says offering inspiratory pressure relief is a game-changer for comfort and ultimately adherence.

Noah and co-investigators then conducted a case series, which has not been published as of Sleep Review press time, of 15 consecutive patients who developed treatment-emergent central sleep apnea (TECSA) while undergoing titration. These patients then tried positive airway pressure therapy with a V-Com to reduce their IPAP while maintaining EPAP. All 15 patients in this pilot had their TECSA resolve—which Noah says gives evidence that treatment-emergent central sleep apnea is the result of positive airway pressure-augmented tidal volumes, which increase minute ventilation and decrease end-tidal carbon dioxide (below the apneic threshold to cause central sleep apnea), particularly when IPAP is greater than EPAP. He plans to investigate this further before potentially submitting this claim to the FDA.

Another study, which also has not been published as of press time, suggests that lowering inspiratory pressure can eliminate the need for CPAP users to need chinstraps. Of 80 consecutive patients who had mouth opening/oral leak during a CPAP titration resolved by a chinstrap, adding a V̇-Com instead eliminated chinstrap need in 85% of cases.

Bernard Hete, PhD, recently left an engineering job he’d held with Respironics since 1992 to join Noah at SleepRes because he finds the evidence of the advantages of lowering inspiratory pressure so compelling.

Hete, now chief technology officer at SleepRes, says, “As an engineer, I must admit that I never really thought about the possibility of reducing IPAP because no one does it. This opens a whole new world of possibilities in patient therapy, perhaps similar in some ways to the situation when CPAP was first introduced commercially in the ’80s.”

Hete adds that other potential benefits of IPAP reduction may be a reduction in work of breathing since less effort would be required during the inspiratory phase to maintain tidal volume.

Potential for New CPAP Algorithms

But adding an accessory like the V-Com, with the extra steps of its acquisition and placement, is probably not a long-term solution—assuming more data supports the emerging evidence that CPAP pressure profiles should be changed to lower IPAP while maintaining EPAP.

At least one CPAP maker is open to rewriting its algorithms.

According to Tom Pontzius, president of CPAP maker React Health (formerly 3B Medical), the preliminary data does support the concept that inspiratory, not expiratory, pressure should be decreased for CPAP use. “Instead of opening the airway on the front end, it’s basically opening the airway on the back end,” he says.

In fact, React Health CPAPs are now part of clinical trials to see if positive airway pressure therapy should be delivered differently. “It is something that we’re studying,” Pontzius says. “There have to be additional clinical evaluations and patient evaluations and following of the science. We are spending some money to do that to make sure.”

Pontzius says the motivation is trying to elucidate the underlying issues to CPAP nonadherence. “When I first got into this business, 25 years ago, there were 50 masks on the market and patients were 50% compliant. Today there are 500 masks on the market and patients are 50% compliant, so is it really the mask?” he asks. For React Health, he says, “If the opportunity lends itself to get better, we are going to look at it and determine from there, does it really make a difference?

“It’s the tip of the spear to kind of change the industry a little bit by working on this…But I think at some point, it’s going to force us as an industry to maybe think that we need to look at different ways, instead of being complacent.”

Other sleep medicine stakeholders ask for more clarity. For instance, sleep physicians have expressed confusion to Sleep Review regarding the terminology, physics, and implications of what changing pressure profiles would look like.

Geoffrey Sleeper, BS, RRT, is a sleep medicine stakeholder who is on board with the concept, particularly as he is the CEO of Bryggs Medical and the inventor of ULTepap, a nasal EPAP only device. He recently contributed to an August 2022 study on the comparison of expiratory pressures generated by four different EPAP devices in a laboratory bench setting.5 There are “dozens and dozens and dozens of articles,” he says, that demonstrate that EPAP devices can singularly and adequately treat obstructive sleep apnea.

“So if that’s true, then this thinking is probably spot-on in that with continuous positive airway pressure, if you’ve dropped the IPAP and not the EPAP you might make it more comfortable for the patient,” Sleeper says. “Higher IPAP is going to slowly increase your tidal volume and that makes it a little uncomfortable.”

What Might We See in the Future?

So where do we go from here?

Gerald E. McGinnis, the founder of Respironics and a retired engineer, says, “We specif[ied] that the powered flow generator should not disturb the patient with the pressure transitions required to provide the desired ventilation. Easier said than done, I’m afraid.” The bottom line, McGinnis says, is the “current technique using simple on/off triggering of IPAP is not adequate technique and should be modified.”

University of Utah’s Farney says, “Ultimately, I would like to see more dynamic modulation of PAP delivery systems to intelligently counteract circumstances that result in airway closure during and after expiration with improved comfort.” He says this would include keeping IPAP low while maintaining “intelligent” EPAP, that is, variable expiratory pressure being delivered at the critical phases during expiration and “maybe during the very first moment of inspiration.”

Strohl says the rediscovered approach to sleep apnea positive airway pressure therapy is really all about providing flexibility. “An obstructive apnea occurs when there is a fall in ventilation and drive to the mechanism that maintains patency and the airway is susceptible (as measured by critical closing pressure),” he says. “Well, the goal is to make PAP therapy for a collapsible airway more comfortable.”

Strohl describes lowering inspiratory pressure via an accessory as “a good, first approach.” But he says that true change requires more education than what is currently provided in a health system that usually waits until a person fails therapy to give intensive coaching. He adds, “Maybe better flow profiles at the start will help.”

Chaunie Brusie, RN, BSN, is a content creator specializing in health, medical, parenting, finance, and travel.

V-Com maker SleepRes LLC paid a fee to expedite this article, which would have otherwise been slated for online and print publication in January 2023.

References

1. Strohl KP, Redline S. Nasal CPAP therapy, upper airway muscle activation, and obstructive sleep apnea. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1986 Sep;134(3):555-8.

2. Mahadevia AK, Onal E, Lopata M. Effects of expiratory positive airway pressure on sleep-induced respiratory abnormalities in patients with hypersomnia-sleep apnea syndrome. Am Rev Respir Dis. 1983 Oct;128(4):708-11.

3. Gugger M, Vock P. Effect of reduced expiratory pressure on pharyngeal size during nasal positive airway pressure in patients with sleep apnoea: evaluation by continuous computed tomography. Thorax. 1992 Oct;47(10):809-13.

4. Resta O, Guido P, Picca V, et al. The role of the expiratory phase in obstructive sleep apnoea. Respir Med. 1999 Mar;93(3):190-5.

5. Sleeper G, Rashidi M, Strohl KP, et al. Comparison of expiratory pressures generated by four different EPAP devices in a laboratory bench setting. Sleep Med. 2022 Aug;96:87-92.

Illustration 12075719 © Radivoje | Dreamstime.com

Early Access Sneak Peek Sponsored by