Roughly one in 10 Americans say they are likely to fall asleep at an inappropriate time and place, including on the job. It’s one thing if their job finds them at a desk all day, where a short lapse in attention may be fairly minor—resulting only in an irate boss perhaps. For a transportation worker, however, it may mean a major accident with multiple fatalities.

Every day we trust transportation workers with our lives—whether they are pilots, train operators, and bus drivers getting us from point A to point B, or truck drivers sharing the road with us to deliver goods. We depend on their alertness. That is why the National Sleep Foundation 2012 poll focused on just how sleepy America’s transportation workers are and how that sleepiness is affecting their work performance, especially in terms of public safety.

As Sanjay R. Patel, MD, MS, lecturer in medicine at the Harvard Medical School and member of the poll task force, points out, “Because only a few seconds of inattention or delay in response times can cause major accidents in the transportation industry, sleep is a particular concern in this field. Add to this the increasing demand placed on the industry to provide services 24/7, and workers in this field face pressures to work extended hours and varying schedules, both of which impede the ability to obtain sufficient sleep on a regular basis.”

ON THE CLOCK

The study of 1,087 respondents (completed via the Web) finds that 11% of pilots, train operators, and bus, taxi, and limo drivers and 8% of truck drivers as well as nontransportation workers are “sleepy.” And that sleepiness translates into job performance problems about three times more often and 45 minutes less sleep per night than their nonsleepy peers. About one-fourth of train operators (26%) and pilots (23%) admit that sleepiness has affected their job performance at least once a week, compared to about one in six nontransportation workers (17%) (Figure 1). Not surprising, among all workers surveyed, train operators and pilots report the most workday sleep dissatisfaction. Almost two-thirds of train operators (57%) and one-half of pilots (50%) say they rarely or never get a good night’s sleep on work nights, compared to 44% of truck drivers and 42% of nontransportation workers. Bus, taxi, and limo drivers, however, report the best workday sleep satisfaction, with 29% saying they rarely or never get a good night’s sleep on work nights.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

Figure 4

For many transportation workers, their schedules are a major contributor to their sleep problems. While 76% of nontransportation workers report working the same schedule every day, only 61% of bus, taxi, and limo drivers, 51% of truck drivers, and 47% of train operators can say the same (Figure 2). Surprisingly, only 6% of pilots report working the same schedule every day and only 10% report working the same days each week.

This day-to-day variability, according to Thomas J. Balkin, PhD, chair of the department of behavioral biology at the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research and chair of the poll task force, makes it difficult for transportation workers—especially pilots—to habituate to a particular sleep/wake schedule, which can greatly interfere with the quality of their sleep, when they sleep, and their level of alertness when they are trying to stay awake. In addition, the survey finds that pilots, truck drivers, and train operators report working longer shifts—10.4 hours, 10.1 hours, and 9.8 hours, respectively—compared to nontransportation workers (8.5 hours) (Figure 3).

Compounding the problem is the fact that those workers who report working a different schedule every day started significantly more shifts between the hours of 3:30 am and 6:30 am, and 10:00 pm and 3:30 am, compared to nontransportation workers. In fact, train operators cited starting a shift between 10:00 pm and 3:30 am significantly 2.7 times more often than every other worker.

As Balkin points out, our brains are hardwired to see the morning light as the time to reset our body’s clock—the ascending phase of our circadian rhythm, while with the dark of night, around 11 pm, we hit the descending phase of the circadian rhythm, making these start times for transportation workers’ shifts disruptive. “Those realities don’t change for shift workers, which is [part of the reason] why shift workers, even people who work steady nights, have difficulty habituating to those schedules.”

OFF THE CLOCK

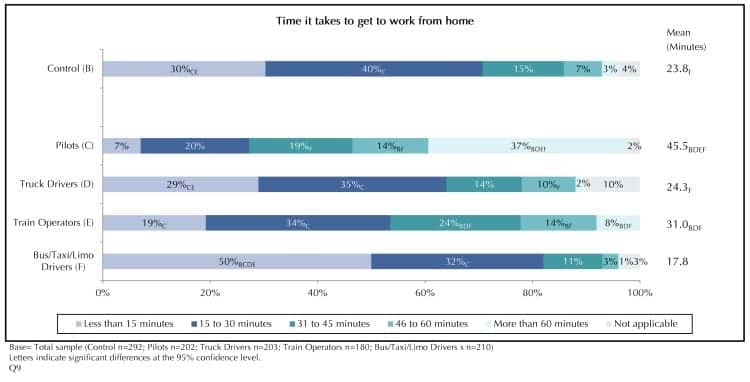

And once they’re off the clock, transportation workers report less time off between shifts than other workers, cutting into available sleep time. While nontransportation workers report having an average of 14.2 hours off between shifts, pilots report 12.9 hours; train operators 12.5; truck drivers 12.1; and bus, taxi, and limo drivers 11.2. Cutting into this shortened time off are the long commutes transportation workers report. Pilots report the longest commutes, with 37% saying it takes them more than an hour to get to work from home (Figure 4). Pilots and train operators have the highest average commute time of 45.5 minutes and 31 minutes, respectively, compared to a 23.8 minute average for nontransportation workers.

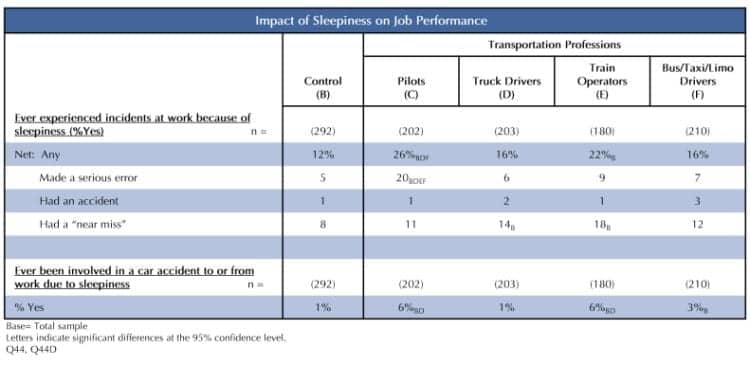

Figure 5

And while this all contributes to on-the-job sleepiness and work-related accidents, it also increases the danger of accidents once transportation workers clock out. The poll found that pilots and train operators are significantly more likely than nontransportation workers—6% each, compared to 1%—to say that they have been involved in a car accident due to sleepiness while commuting (Figure 5).

“This is similar actually to [recent studies looking at] medical residents—that they are more likely to have accidents coming from work after a long shift. It makes perfect sense. It’s not as though the physiology is going to change just because you are off work. At the end of a long shift, if you haven’t gotten adequate sleep and you’re going to go home and sleep, that may be a time of particular vulnerability,” said Balkin.

Patel points out that the concern here is that while the transportation industry has focused on preventing sleepiness-induced accidents while at work, the same attention has not been paid to how workers are also at elevated risk after they leave work. He recommends that employer safety plans consider including opportunities for those who are sleep deprived to take a nap at the end of a shift before driving home.

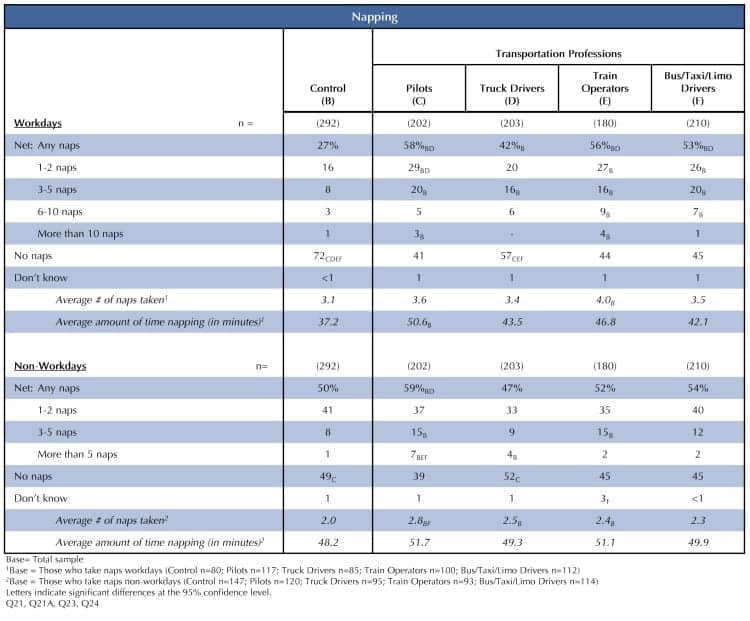

On the positive side, these workers do recognize their need for sleep. If given 1 more hour off between work shifts, more than half of pilots (56%) and train operators (54%) report that they would use that hour for sleep. In addition, when given the opportunity, transportation workers report taking more naps than other workers. More than one-half of pilots (58%) and train operators (56%) take at least one nap on work days, compared to about one-fourth of nontransportation workers (27%). About one in five pilots (20%), bus, taxi, and limo drivers (20%), truck drivers (16%), and train operators (16%) say they take three to five naps during the work week (Figure 6). And on work days, 50% of the pilots surveyed, as well as 42% of truck drivers, 33% of train operators, and 24% of bus, taxi, and limo drivers, report napping during work hours in the past 2 weeks, compared to 19% of nontransportation workers. Of those who took naps on workdays, significantly more pilots (75%), truck drivers (65%), and bus, taxi, or limo drivers (62%) say naps during breaks at work are sanctioned by their employers compared to other workers (30%).

This finding came as no surprise to Patel. “Not only is this group more sleep deprived, but they and their employers are much more aware of the utility of using naps to improve performance than other industries,” he says. “Naps can play an important role in allowing individuals to obtain additional sleep. They can be viewed as a safety valve when insufficient sleep is obtained between shifts. This can be particularly helpful for shift workers where circadian biology may prevent them from being able to sleep effectively during their time off work.”

WHAT’S TO BE DONE?

So what’s to be done? Awareness of the problem has been heightened within the transportation industry in recent years, especially within the trucking industry; however, there is still a ways to go. While government regulations are needed to maintain minimum standards and to hold violators responsible, companies themselves are in the best position to develop policies that directly affect workers to ensure adequate opportunities for sleep within their specific scheduling needs as well as to develop a culture in the workplace where, as Patel puts it, “it is no more acceptable to work sleep deprived as it is to work intoxicated.”

Figure 6

“Employers need to realize that ensuring their employees obtain adequate sleep is not only important for optimizing worker productivity, but is also a requirement to maintain the high level of safety that the public expects in this industry,” adds Patel.

Still, transportation workers themselves need to be held responsible for ensuring that they have obtained adequate sleep before they clock in and put others’ lives in their hands.

“We can always devise the perfect or optimal schedule, but if the person doesn’t take advantage of that schedule and do what they are supposed to do, and be a good citizen and sleep when they are supposed to sleep, then it is all for naught,” says Balkin.

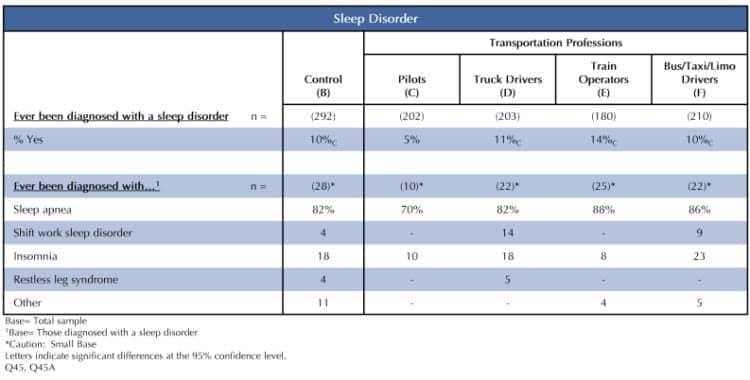

SLEEP INDUSTRY

The reality is that most of these workers aren’t finding their way into America’s sleep labs for help. Most don’t have a sleep disorder per se—only about one in 10 train operators (14%), truck drivers (11%), and bus, taxi, or limo drivers (10%), and only one in 20 pilots (5%) report ever having been diagnosed with a sleep disorder compared to 10% of nontransportation workers (Figure 7). However, sleep professionals treating patients who work in the transportation industry need to be aware of the unique demands these patients’ job requirements put on them.

Figure 7

“Sleep professionals need to take a detailed occupational history from anyone complaining of sleep-related symptoms, including length of shift, timing of shift, and variability of shift. In addition, they need to ask about commuting times,” says Patel.

“Less than 80% of nontransportation workers said they make an effort to obtain adequate sleep before a work shift. This is unacceptable,” says Patel. “We need to convince employers and the public that adequate sleep is necessary to get our work force as productive as it can be.”

Alison Werner is associate editor of Sleep Review. She can be reached at [email protected].