The growing number of children who are becoming obese continues to escalate the incidence of sleep apnea in our youngest patients. “Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a frequent but underdiagnosed problem in children reportedly affecting up to 3% of children in the US” and is estimated to slightly impact as many as 12% of children who snore.1 Though obesity certainly contributes to OSA in our children, one of the most frequent causes of OSA in young children is adenotonsillar hypertrophy. The case of a 5-year-old patient presenting with ADHD/ADD, seizure disorder, and OSA symptoms after adenotonsillectomy (TNA) illustrates the necessity for patience and persistence among varied physician disciplines in order to achieve successful, long-term patient outcomes.

BACKGROUND

Consequences and problems that children and families face as a result of OSA may range from failure to thrive, enuresis, attention deficit disorder (ADD), behavioral problems, poor academic performance, and even cardiopulmonary disease.2 The advice presented by Doctors C. Won, Jee H. Kim, and Christian Guilleminault in a 2007 article emphasizes the need for a multidisciplinary approach to solving pediatric OSA and the problems affiliated with the disorder. The authors write: “It is important to mention that when evaluating a child suspected of having sleep-disordered breathing a multidisciplinary approach involving a sleep specialist, otolaryngologist, maxillofacial surgeon, and orthodontist should be utilized. Children with OSA often have enlarged tonsillar and adenoid tissue in the setting of an already narrowed or floppy airway. Therefore, even though TNA has a high initial success rate for improving OSA and associated symptoms of OSA, if not curative, it may do little to affect craniofacial development in the long term, and the child remains at risk for worsening OSA in adulthood. The multidisciplinary approach assures a comprehensive plan to address all aspects of the child’s orofacial anatomy and positively affects craniofacial and upper airway development in a child at risk for OSA in adolescence or adulthood.”1

Though TNA is routinely performed on children 24 months and beyond, many parents are reluctant to have their child undergo surgery. One way to clearly demonstrate the need (to parents) for surgical intervention is to simply test the child in a sleep lab.

Although the role of a preoperative polysomnogram (PSG) is clearly indicated in children with tonsillar hypertrophy and sleep-disordered breathing, it is not always ordered in evaluating a child. When PSG testing is recommended to the parents, it is important that they research the regional sleep testing facilities that are appropriate for pediatric testing. The sleep specialists, the technical staff, and certainly the facility are among the primary considerations in placing a child for testing.

Though potential parental fear is certainly valid and very real, it is important to enlist parental cooperation and commitment to primary and secondary treatment options early in the process, including discussion of postoperative PSG for children with a high likelihood of residual OSA. Research supports conducting postoperative PSG: “Considering the number of TNAs performed each year, this still leaves a large number of post-operative children with residual OSA. There is a paucity of data to predict surgical success or failure, therefore, a post-operative PSG is encouraged in all patients six weeks to three months after surgery, particularly in children in whom there is a high likelihood of residual OSA, such as in cases of a narrow mandible or maxilla, obesity, neuromuscular disorder, trisomy, or craniofacial abnormalities.”1

CASE REPORT

Lawrence T. Ch’ien, MD, DABSM, is a practicing pediatric neurologist and sleep specialist in Chattanooga, Tenn, who follows and treats dozens of pediatric sleep patients. The practice is made up of mainly neurology and sleep disorder patients. The case of one particular child, who was being treated for ADHD/ADD, seizure disorder, and OSA, involves a 5-year-old male patient with sleep-disordered breathing and apneic episodes that were present even after adenotonsillectomy. His presentation included a past medical history of loud snoring, daytime hyperactivity, and various behavioral difficulties reported by his parents.

|

The patient’s mother reported that the child snored every night despite his TNA surgery and that she routinely witnessed apneas. Subjectively, the child reported having daily hypersomnolence, lethargy, yet also hyperactivity at times. Estimated sleep latency each night ranged from 20 to 30 minutes regularly, and the mother reported that he had up to five nocturnal awakenings. The boy reported positive dream recall upon awakening most days and also that his sleep generally felt restorative upon awakening.

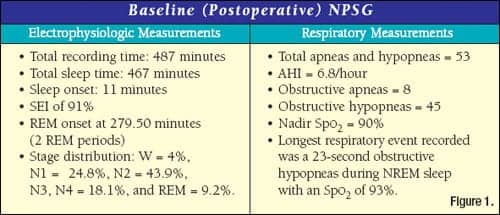

Prescriptions administered nightly and during the study in the lab included oxcarbazepine 150 bid, methylphenidate (Concerta) 54 mg, and imipramine 50 mg at bedtime to control nocturnal seizures and other parasomnias. The child’s reported bedtime is typically 9:00 pm to 10:00 pm and usual wake time is 5:30 am to 6:00 am. From the age of 4 to 5 years old, there was a 15-pound weight gain. Height 50 inches and weight 84 pounds. The soft palate’s presentation was low and the oropharynx presented as consistent with the recent TNA. The child reports difficulty breathing through his nose, and typically four to five nocturnal awakenings. He underwent a postoperative polysomnogram that revealed the data in Figure 1.

POLYSOMNOGRAPHY WITH NCPAP

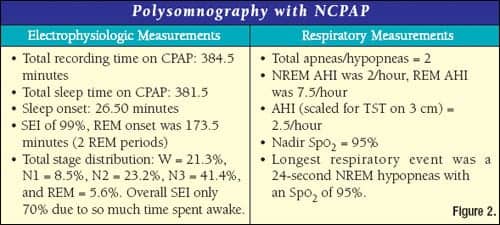

During the nCPAP study, all snoring was extinguished, and the child tolerated the procedure very well. At lights out, the child had been properly fitted with a size small, ResMed Mirage full-face mask, and was able to initiate sleep without significant delay or distress. Notable slow wave rebound was observed, and an early REM onset did not occur (see Figure 2 for study data). No parasomnias or grossly abnormal behavior occurred during the study, and the child’s mother stayed overnight in the lab to provide assistance to the staff in comforting the child on several awakenings.

DIAGNOSIS AND TREATMENT PLAN

|

This child was diagnosed at 5 years of age with postoperative, residual OSA, and ADHD. Over the course of the next few years, the child’s CPAP pressure was first gradually increased to 6 cm at 5 months post testing (during routine follow-up). After establishing the child on nightly CPAP and regular medicine, his hyperactivity improved and was reported by the mother to be much better controlled through a combination of medicine and CPAP. By the time the

patient reached 9 years of age, his CPAP pressure had been increased to 11 cm. The child’s mother reported that the periods of best compliance were when both medicines and CPAP were utilized on a daily basis. She also reported that these periods always corresponded to improvements in the classroom. This progress encouraged her to see that he remained compliant. Since the age of 9, the boy has been able to apply his own mask and headgear when using CPAP nightly, and his care is still managed by regularly scheduled follow-ups.

Prior to postoperative testing, polysomnographic testing, and the initiation of nCPAP therapy, the child had exhibited disruptive behavior in school, difficulty in focusing on tasks, disrupted sleep architecture, parasomnias, and several nightly awakenings. The combination of nCPAP therapy and medicine was effective in making improvements to his quality of sleep and noticeably curtailing the ADHD behaviors that were disruptive to his education and ability to take instruction. Ch’ien attributes the progress and success in his case to a group effort among well-qualified pediatric specialists, the mother, and a very positive experience while in the lab during his titration study.

DISCUSSION

The number of children being diagnosed with both OSA and ADHD continues to grow, and it is very important to their care that a well-communicated and orchestrated continuum of care be followed as demonstrated in the case of Ch’ien’s patient. In children who have had adenotonsillectomy as intervention for OSA, other issues that are associated with poor-quality sleep, such as enuresis, snoring, and behavioral problems, often improve as the result of surgery. The best advised assessment of the efficacy of adenotonsillectomy in children is the postoperative sleep study.

Robert Lindsey, MS, RPSGT, is the administrator of Specialists in Pulmonary Care and Sleep Medicine, Chattanooga, Tenn, and is a member of the Editorial Advisory Board of Sleep Review. Lawrence T. Ch’ien, MD, DABSM, is a pediatric neurologist and sleep specialist in private practice, in Chattanooga, Tenn.

REFERENCES

- Won C, Kim JH, Guilleminault C. Considerations for managing pediatric sleep apnea. U.S. Neurological Disease. 2007;4(I):18-21.

- Chan J, Edman JC, Koltai PJ. Obstructive sleep apnea in children. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1147-54.